HTTP/2

Introduction

HTTP/2 was the first major update to the main transport protocol of the web in nearly 20 years. It arrived with a wealth of expectations: it promised a free performance boost with no downsides. More than that, we could stop doing all the hacks and work arounds that HTTP/1.1 forced us into, due to its inefficiencies. Bundling, spriting, inlining, and even sharding domains would all become anti-patterns in an HTTP/2 world, as improved performance would be provided by default.

This meant that even those without the skills and resources to concentrate on web performance would suddenly have performant websites. However, the reality has been, as ever, a little more nuanced than that. It has been over four years since the formal approval of HTTP/2 as a standard in May 2015 as RFC 7540, so now is a good time to look over how this relatively new technology has fared in the real world.

What is HTTP/2?

For those not familiar with the technology, a bit of background is helpful to make the most of the metrics and findings in this chapter. Up until recently, HTTP has always been a text-based protocol. An HTTP client like a web browser opened a TCP connection to a server, and then sent an HTTP command like GET /index.html to ask for a resource.

This was enhanced in HTTP/1.0 to add HTTP headers, so various pieces of metadata could be included in addition to the request, such as what browser it is, the formats it understands, etc. These HTTP headers were also text-based and separated by newline characters. Servers parsed the incoming requests by reading the request and any HTTP headers line by line, and then the server responded with its own HTTP response headers in addition to the actual resource being requested.

The protocol seemed simple, but it also came with limitations. Because HTTP was essentially synchronous, once an HTTP request had been sent, the whole TCP connection was basically off limits to anything else until the response had been returned, read, and processed. This was incredibly inefficient and required multiple TCP connections (browsers typically use 6) to allow a limited form of parallelization.

That in itself brings its own issues as TCP connections take time and resources to set up and get to full efficiency, especially when using HTTPS, which requires additional steps to set up the encryption. HTTP/1.1 improved this somewhat, allowing reuse of TCP connections for subsequent requests, but still did not solve the parallelization issue.

Despite HTTP being text-based, the reality is that it was rarely used to transport text, at least in its raw format. While it was true that HTTP headers were still text, the payloads themselves often were not. Text files like HTML, JS, and CSS are usually compressed for transport into a binary format using Gzip, Brotli, or similar. Non-text files like images and videos are served in their own formats. The whole HTTP message is then often wrapped in HTTPS to encrypt the messages for security reasons.

So, the web had basically moved on from text-based transport a long time ago, but HTTP had not. One reason for this stagnation was because it was so difficult to introduce any breaking changes to such a ubiquitous protocol like HTTP (previous efforts had tried and failed). Many routers, firewalls, and other middleboxes understood HTTP and would react badly to major changes to it. Upgrading them all to support a new version was simply not possible.

In 2009, Google announced that they were working on an alternative to the text-based HTTP called SPDY, which has since been deprecated. This would take advantage of the fact that HTTP messages were often encrypted in HTTPS, which prevents them being read and interfered with en route.

Google controlled one of the most popular browsers (Chrome) and some of the most popular websites (Google, YouTube, Gmail…etc.) - so both ends of the connection when both were used together. Google’s idea was to pack HTTP messages into a proprietary format, send them across the internet, and then unpack them on the other side. The proprietary format, SPDY, was binary-based rather than text-based. This solved some of the main performance problems with HTTP/1.1 by allowing more efficient use of a single TCP connection, negating the need to open the six connections that had become the norm under HTTP/1.1.

By using SPDY in the real world, they were able to prove that it was more performant for real users, and not just because of some lab-based experimental results. After rolling out SPDY to all Google websites, other servers and browser started implementing it, and then it was time to standardize this proprietary format into an internet standard, and thus HTTP/2 was born.

HTTP/2 has the following key concepts:

- Binary format

- Multiplexing

- Flow control

- Prioritization

- Header compression

- Push

Binary format means that HTTP/2 messages are wrapped into frames of a pre-defined format, making HTTP messages easier to parse and would no longer require scanning for newline characters. This is better for security as there were a number of exploits for previous versions of HTTP. It also means HTTP/2 connections can be multiplexed. Different frames for different streams can be sent on the same connection without interfering with each other as each frame includes a stream identifier and its length. Multiplexing allows much more efficient use of a single TCP connection without the overhead of opening additional connections. Ideally we would open a single connection per domain—or even for multiple domains!

Having separate streams does introduce some complexities along with some potential benefits. HTTP/2 needs the concept of flow control to allow the different streams to send data at different rates, whereas previously, with only one response in flight at any one time, this was controlled at a connection level by TCP flow control. Similarly, prioritization allows multiple requests to be sent together, but with the most important requests getting more of the bandwidth.

Finally, HTTP/2 introduced two new concepts: header compression and HTTP/2 push. Header compression allowed those text-based HTTP headers to be sent more efficiently, using an HTTP/2-specific HPACK format for security reasons. HTTP/2 push allowed more than one response to be sent in answer to a request, enabling the server to “push” resources before a client was even aware it needed them. Push was supposed to solve the performance workaround of having to inline resources like CSS and JavaScript directly into HTML to prevent holding up the page while those resources were requested. With HTTP/2 the CSS and JavaScript could remain as external files but be pushed along with the initial HTML, so they were available immediately. Subsequent page requests would not push these resources, since they would now be cached, and so would not waste bandwidth.

This whistle-stop tour of HTTP/2 gives the main history and concepts of the newish protocol. As should be apparent from this explanation, the main benefit of HTTP/2 is to address performance limitations of the HTTP/1.1 protocol. There were also security improvements as well - perhaps most importantly in being to address performance issues of using HTTPS since HTTP/2, even over HTTPS, is often much faster than plain HTTP. Other than the web browser packing the HTTP messages into the new binary format, and the web server unpacking it at the other side, the core basics of HTTP itself stayed roughly the same. This means web applications do not need to make any changes to support HTTP/2 as the browser and server take care of this. Turning it on should be a free performance boost, therefore adoption should be relatively easy. Of course, there are ways web developers can optimize for HTTP/2 to take full advantage of how it differs.

Adoption of HTTP/2

As mentioned above, internet protocols are often difficult to adopt since they are ingrained into so much of the infrastructure that makes up the internet. This makes introducing any changes slow and difficult. IPv6 for example has been around for 20 years but has struggled to be adopted.

HTTP/2 however, was different as it was effectively hidden in HTTPS (at least for the browser uses cases), removing barriers to adoption as long as both the browser and server supported it. Browser support has been very strong for some time and the advent of auto updating evergreen browsers has meant that an estimated 95% of global users now support HTTP/2.

Our analysis is sourced from the HTTP Archive, which tests approximately 5 million of the top desktop and mobile websites in the Chrome browser. (Learn more about our methodology.)

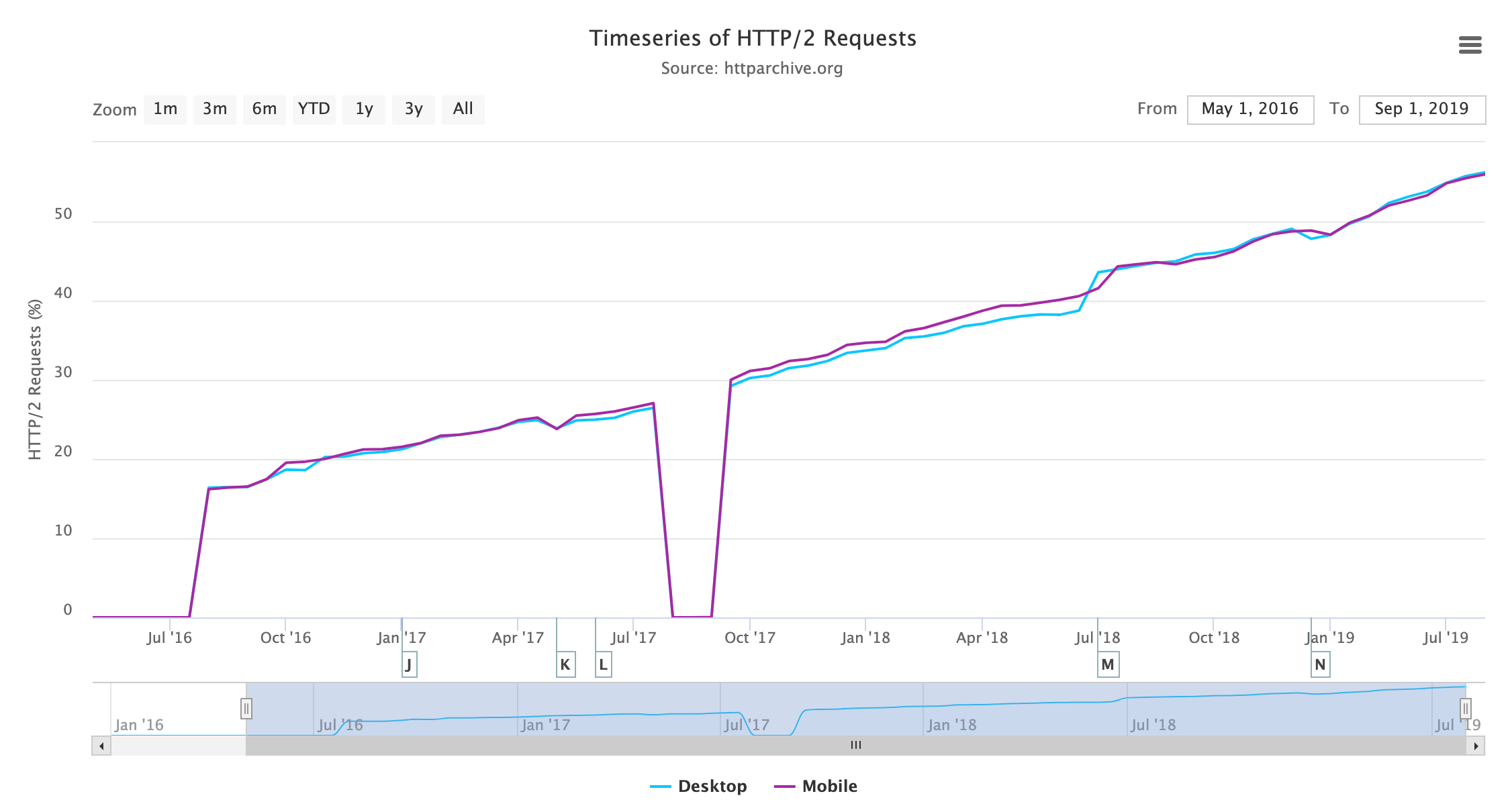

The results show that HTTP/2 usage is now the majority protocol-an impressive feat just 4 short years after formal standardization! Looking at the breakdown of all HTTP versions by request we see the following:

| Protocol | Desktop | Mobile | Both |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5.60% | 0.57% | 2.97% | |

| HTTP/0.9 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| HTTP/1.0 | 0.08% | 0.05% | 0.06% |

| HTTP/1.1 | 40.36% | 45.01% | 42.79% |

| HTTP/2 | 53.96% | 54.37% | 54.18% |

Figure 20.3 shows that HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2 are the versions used by the vast majority of requests as expected. There is only a very small number of requests on the older HTTP/1.0 and HTTP/0.9 protocols. Annoyingly, there is a larger percentage where the protocol was not correctly tracked by the HTTP Archive crawl, particularly on desktop. Digging into this has shown various reasons, some of which can be explained and some of which can’t. Based on spot checks, they mostly appear to be HTTP/1.1 requests and, assuming they are, desktop and mobile usage is similar.

Despite there being a little larger percentage of noise than we’d like, it doesn’t alter the overall message being conveyed here. Other than that, the mobile/desktop similarity is not unexpected; HTTP Archive tests with Chrome, which supports HTTP/2 for both desktop and mobile. Real-world usage may have slightly different stats with some older usage of browsers on both, but even then support is widespread, so we would not expect a large variation between desktop and mobile.

At present, HTTP Archive does not track HTTP over QUIC (soon to be standardized as HTTP/3) separately, so these requests are currently listed under HTTP/2, but we’ll look at other ways of measuring that later in this chapter.

Looking at the number of requests will skew the results somewhat due to popular requests. For example, many sites load Google Analytics, which does support HTTP/2, and so would show as an HTTP/2 request, even if the embedding site itself does not support HTTP/2. On the other hand, popular websites tend to support HTTP/2 are also underrepresented in the above stats as they are only measured once (e.g. “google.com” and “obscuresite.com” are given equal weighting). There are lies, damn lies, and statistics.

However, our findings are corroborated by other sources, like Mozilla’s telemetry, which looks at real-world usage through the Firefox browser.

| Protocol | Desktop | Mobile | Both |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.09% | 0.08% | 0.08% | |

| HTTP/1.0 | 0.09% | 0.08% | 0.09% |

| HTTP/1.1 | 62.36% | 63.92% | 63.22% |

| HTTP/2 | 37.46% | 35.92% | 36.61% |

It is still interesting to look at home pages only to get a rough figure on the number of sites that support HTTP/2 (at least on their home page). Figure 20.4 shows less support than overall requests, as expected, at around 36%.

HTTP/2 is only supported by browsers over HTTPS, even though officially HTTP/2 can be used over HTTPS or over unencrypted non-HTTPS connections. As mentioned previously, hiding the new protocol in encrypted HTTPS connections prevents networking appliances which do not understand this new protocol from interfering with (or rejecting!) its usage. Additionally, the HTTPS handshake allows an easy method of the client and server agreeing to use HTTP/2.

| Protocol | Desktop | Mobile | Both |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.09% | 0.10% | 0.09% | |

| HTTP/1.0 | 0.06% | 0.06% | 0.06% |

| HTTP/1.1 | 45.81% | 44.31% | 45.01% |

| HTTP/2 | 54.04% | 55.53% | 54.83% |

The web is moving to HTTPS, and HTTP/2 turns the traditional argument of HTTPS being bad for performance almost completely on its head. Not every site has made the transition to HTTPS, so HTTP/2 will not even be available to those that have not. Looking at just those sites that use HTTPS, in Figure 20.5 we do see a higher adoption of HTTP/2 at around 55%, similar to the percent of all requests in Figure 20.2.

We have shown that browser support for HTTP/2 is strong and that there is a safe road to adoption, so why doesn’t every site (or at least every HTTPS site) support HTTP/2? Well, here we come to the final item for support we have not measured yet: server support.

This is more problematic than browser support as, unlike modern browsers, servers often do not automatically upgrade to the latest version. Even when the server is regularly maintained and patched, that will often just apply security patches rather than new features like HTTP/2. Let’s look first at the server HTTP headers for those sites that do support HTTP/2.

| Server | Desktop | Mobile | Both |

|---|---|---|---|

| nginx | 34.04% | 32.48% | 33.19% |

| cloudflare | 23.76% | 22.29% | 22.97% |

| Apache | 17.31% | 19.11% | 18.28% |

| 4.56% | 5.13% | 4.87% | |

| LiteSpeed | 4.11% | 4.97% | 4.57% |

| GSE | 2.16% | 3.73% | 3.01% |

| Microsoft-IIS | 3.09% | 2.66% | 2.86% |

| openresty | 2.15% | 2.01% | 2.07% |

| … | … | … | … |

Nginx provides package repositories that allow ease of installing or upgrading to the latest version, so it is no surprise to see it leading the way here. Cloudflare is the most popular CDN and enables HTTP/2 by default, so again it is not surprising to see it hosts a large percentage of HTTP/2 sites. Incidently, Cloudflare uses a heavily customized version of nginx as their web server. After those, we see Apache at around 20% of usage, followed by some servers who choose to hide what they are, and then the smaller players such as LiteSpeed, IIS, Google Servlet Engine, and openresty, which is nginx based.

What is more interesting is those servers that that do not support HTTP/2:

| Server | Desktop | Mobile | Both |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apache | 46.76% | 46.84% | 46.80% |

| nginx | 21.12% | 21.33% | 21.24% |

| Microsoft-IIS | 11.30% | 9.60% | 10.36% |

| 7.96% | 7.59% | 7.75% | |

| GSE | 1.90% | 3.84% | 2.98% |

| cloudflare | 2.44% | 2.48% | 2.46% |

| LiteSpeed | 1.02% | 1.63% | 1.36% |

| openresty | 1.22% | 1.36% | 1.30% |

| … | … | … | … |

Some of this will be non-HTTPS traffic that would use HTTP/1.1 even if the server supported HTTP/2, but a bigger issue is those that do not support HTTP/2 at all. In these stats, we see a much greater share for Apache and IIS, which are likely running older versions.

For Apache in particular, it is often not easy to add HTTP/2 support to an existing installation, as Apache does not provide an official repository to install this from. This often means resorting to compiling from source or trusting a third-party repository, neither of which is particularly appealing to many administrators.

Only the latest versions of Linux distributions (RHEL and CentOS 8, Ubuntu 18 and Debian 9) come with a version of Apache which supports HTTP/2, and many servers are not running those yet. On the Microsoft side, only Windows Server 2016 and above supports HTTP/2, so again those running older versions cannot support this in IIS.

Merging these two stats together, we can see the percentage of installs per server, that use HTTP/2:

| Server | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

| cloudflare | 85.40% | 83.46% |

| LiteSpeed | 70.80% | 63.08% |

| openresty | 51.41% | 45.24% |

| nginx | 49.23% | 46.19% |

| GSE | 40.54% | 35.25% |

| 25.57% | 27.49% | |

| Apache | 18.09% | 18.56% |

| Microsoft-IIS | 14.10% | 13.47% |

| … | … | … |

It’s clear that Apache and IIS fall way behind with 18% and 14% of their installed based supporting HTTP/2, which has to be (at least in part) a consequence of it being more difficult to upgrade them. A full operating system upgrade is often required for many servers to get this support easily. Hopefully this will get easier as new versions of operating systems become the norm.

None of this is a comment on the HTTP/2 implementations here (I happen to think Apache has one of the best implementations), but more about the ease of enabling HTTP/2 in each of these servers–or lack thereof.

Impact of HTTP/2

The impact of HTTP/2 is much more difficult to measure, especially using the HTTP Archive methodology. Ideally, sites should be crawled with both HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2 and the difference measured, but that is not possible with the statistics we are investigating here. Additionally, measuring whether the average HTTP/2 site is faster than the average HTTP/1.1 site introduces too many other variables that require a more exhaustive study than we can cover here.

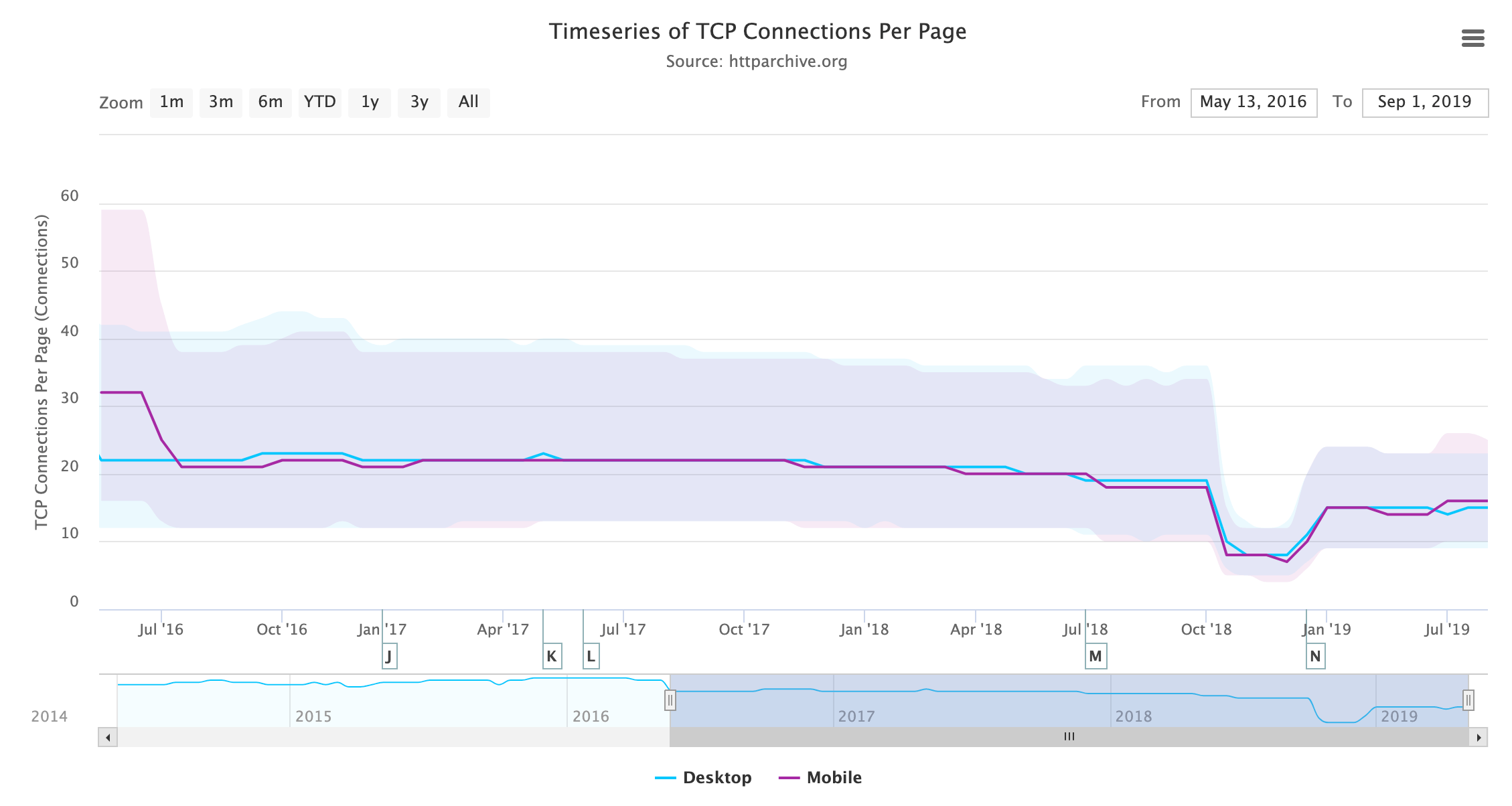

One impact that can be measured is in the changing use of HTTP now that we are in an HTTP/2 world. Multiple connections were a workaround with HTTP/1.1 to allow a limited form of parallelization, but this is in fact the opposite of what usually works best with HTTP/2. A single connection reduces the overhead of TCP setup, TCP slow start, and HTTPS negotiation, and it also allows the potential of cross-request prioritization.

HTTP Archive measures the number of TCP connections per page, and that is dropping steadily as more sites support HTTP/2 and use its single connection instead of six separate connections.

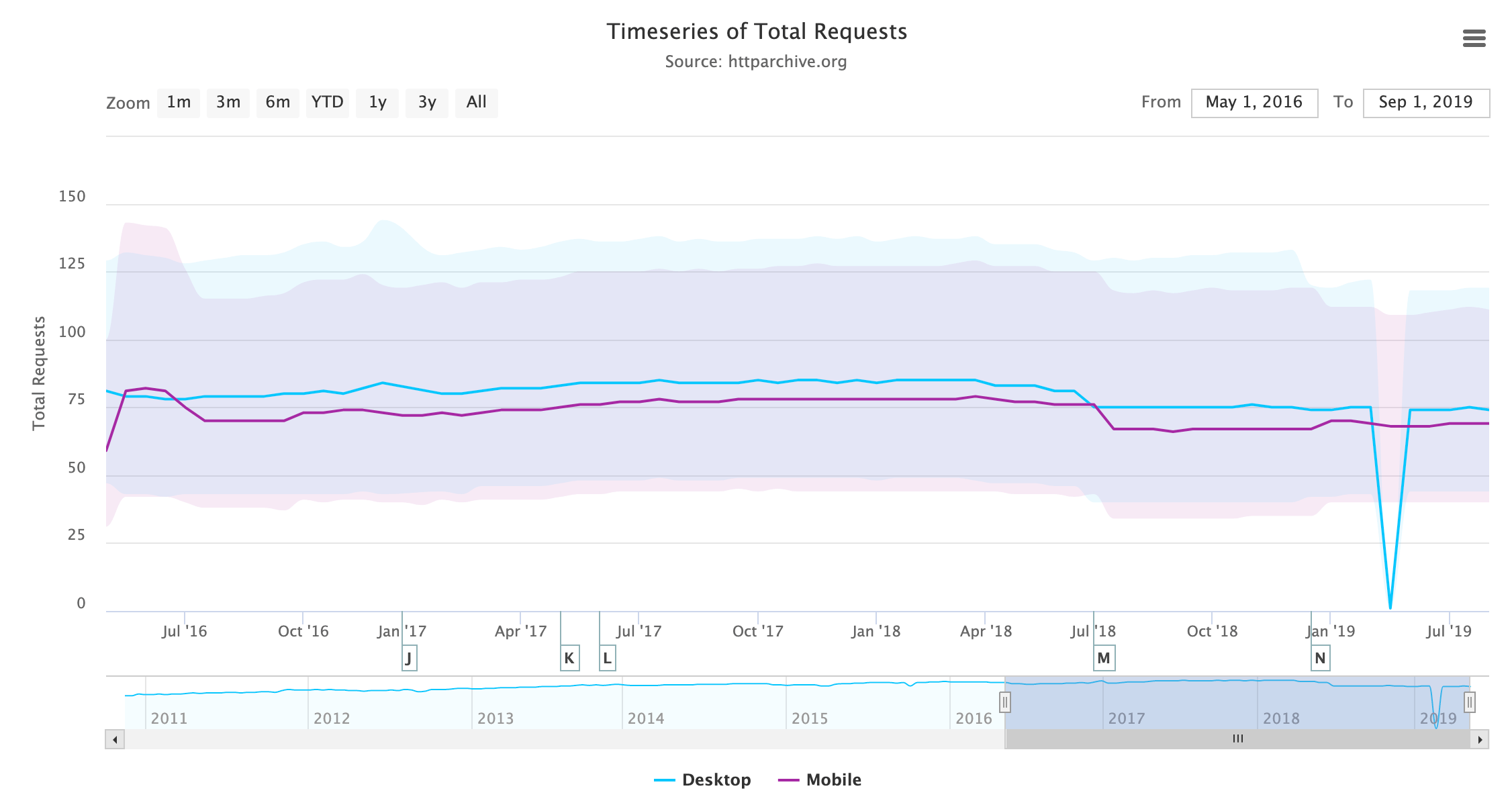

Bundling assets to obtain fewer requests was another HTTP/1.1 workaround that went by many names: bundling, concatenation, packaging, spriting, etc. This is less necessary when using HTTP/2 as there is less overhead with requests, but it should be noted that requests are not free in HTTP/2, and those that experimented with removing bundling completely have noticed a loss in performance. Looking at the number of requests loaded per page over time, we do see a slight decrease in requests, rather than the expected increase.

This low rate of change can perhaps be attributed to the aforementioned observations that bundling cannot be removed (at least, not completely) without a negative performance impact and that many build tools currently bundle for historical reasons based on HTTP/1.1 recommendations. It is also likely that many sites may not be willing to penalize HTTP/1.1 users by undoing their HTTP/1.1 performance hacks just yet, or at least that they do not have the confidence (or time!) to feel that this is worthwhile.

The fact that the number of requests is staying roughly static is interesting, given the ever-increasing page weight, though perhaps this is not entirely related to HTTP/2.

HTTP/2 Push

HTTP/2 push has a mixed history despite being a much-hyped new feature of HTTP/2. The other features were basically performance improvements under the hood, but push was a brand new concept that completely broke the single request to single response nature of HTTP. It allowed extra responses to be returned; when you asked for the web page, the server could respond with the HTML page as usual, but then also send you the critical CSS and JavaScript, thus avoiding any additional round trips for certain resources. It would, in theory, allow us to stop inlining CSS and JavaScript into our HTML, and still get the same performance gains of doing so. After solving that, it could potentially lead to all sorts of new and interesting use cases.

The reality has been, well, a bit disappointing. HTTP/2 push has proved much harder to use effectively than originally envisaged. Some of this has been due to the complexity of how HTTP/2 push works, and the implementation issues due to that.

A bigger concern is that push can quite easily cause, rather than solve, performance issues. Over-pushing is a real risk. Often the browser is in the best place to decide what to request, and just as crucially when to request it but HTTP/2 push puts that responsibility on the server. Pushing resources that a browser already has in its cache, is a waste of bandwidth (though in my opinion so is inlining CSS but that gets must less of a hard time about that than HTTP/2 push!).

Proposals to inform the server about the status of the browser cache have stalled especially on privacy concerns. Even without that problem, there are other potential issues if push is not used correctly. For example, pushing large images and therefore holding up the sending of critical CSS and JavaScript will lead to slower websites than if you’d not pushed at all!

There has also been very little evidence to date that push, even when implemented correctly, results in the performance increase it promised. This is an area that, again, the HTTP Archive is not best placed to answer, due to the nature of how it runs (a crawl of popular sites using Chrome in one state), so we won’t delve into it too much here. However, suffice to say that the performance gains are far from clear-cut and the potential problems are real.

Putting that aside let’s look at the usage of HTTP/2 push.

| Client | Sites Using HTTP/2 Push | Sites Using HTTP/2 Push (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Desktop | 22,581 | 0.52% |

| Mobile | 31,452 | 0.59% |

| Client | Avg Pushed Requests | Avg KB Pushed |

|---|---|---|

| Desktop | 7.86 | 162.38 |

| Mobile | 6.35 | 122.78 |

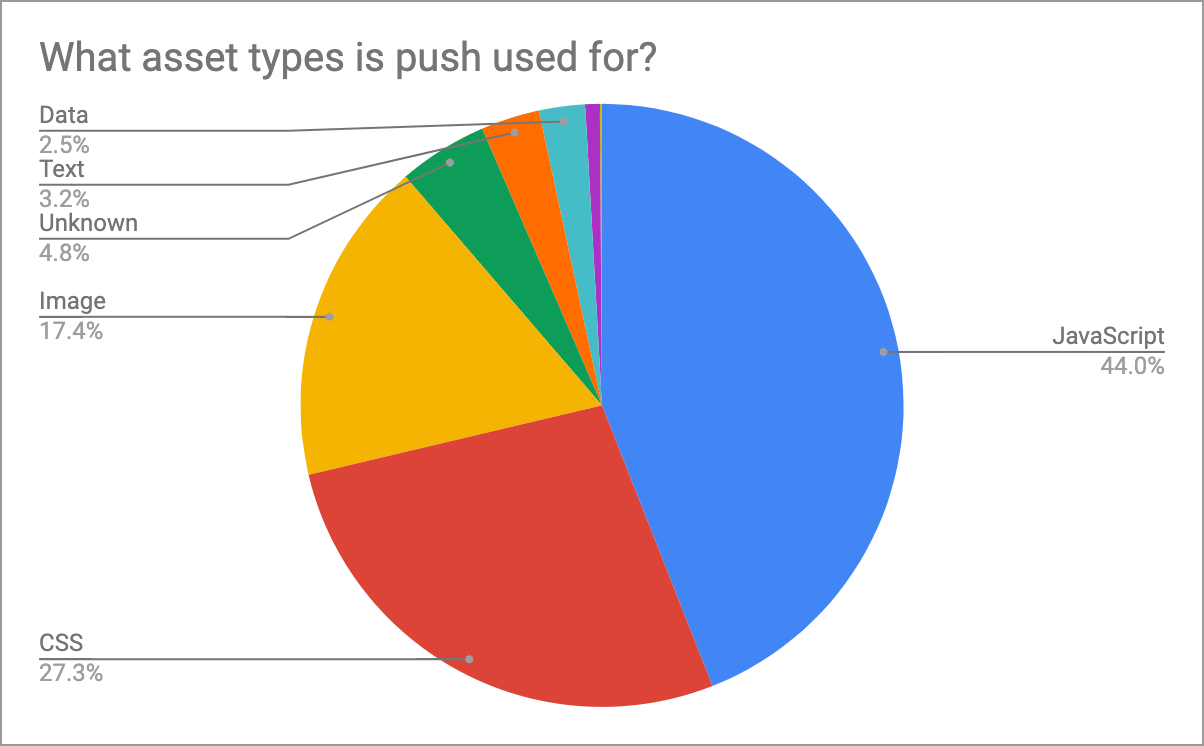

These stats show that the uptake of HTTP/2 push is very low, most likely because of the issues described previously. However, when sites do use push, they tend to use it a lot rather than for one or two assets as shown in Figure 20.12.

This is a concern as previous advice has been to be conservative with push and to “push just enough resources to fill idle network time, and no more”. The above statistics suggest many resources of a significant combined size are pushed.

Figure 20.13 shows us which assets are most commonly pushed. JavaScript and CSS are the overwhelming majority of pushed items, both by volume and by bytes. After this, there is a ragtag assortment of images, fonts, and data. At the tail end we see around 100 sites pushing video, which may be intentional, or it may be a sign of over-pushing the wrong types of assets!

One concern raised by some is that HTTP/2 implementations have repurposed the preload HTTP link header as a signal to push. One of the most popular uses of the preload resource hint is to inform the browser of late-discovered resources, like fonts and images, that the browser will not see until the CSS has been requested, downloaded, and parsed. If these are now pushed based on that header, there was a concern that reusing this may result in a lot of unintended pushes.

However, the relatively low usage of fonts and images may mean that risk is not being seen as much as was feared. <link rel="preload" ... > tags are often used in the HTML rather than HTTP link headers and the meta tags are not a signal to push. Statistics in the Resource Hints chapter show that fewer than 1% of sites use the preload HTTP link header, and about the same amount use preconnect which has no meaning in HTTP/2, so this would suggest this is not so much of an issue. Though there are a number of fonts and other assets being pushed, which may be a signal of this.

As a counter argument to those complaints, if an asset is important enough to preload, then it could be argued these assets should be pushed if possible as browsers treat a preload hint as very high priority requests anyway. Any performance concern is therefore (again arguably) at the overuse of preload, rather than the resulting HTTP/2 push that happens because of this.

To get around this unintended push, you can provide the nopush attribute in your preload header:

link: </assets/jquery.js>; rel=preload; as=script; nopush5% of preload HTTP headers do make use of this attribute, which is higher than I would have expected as I would have considered this a niche optimization. Then again, so is the use of preload HTTP headers and/or HTTP/2 push itself!

HTTP/2 Issues

HTTP/2 is mostly a seamless upgrade that, once your server supports it, you can switch on with no need to change your website or application. You can optimize for HTTP/2 or stop using HTTP/1.1 workarounds as much, but in general, a site will usually work without needing any changes—it will just be faster. There are a couple of gotchas to be aware of, however, that can impact any upgrade, and some sites have found these out the hard way.

One cause of issues in HTTP/2 is the poor support of HTTP/2 prioritization. This feature allows multiple requests in progress to make the appropriate use of the connection. This is especially important since HTTP/2 has massively increased the number of requests that can be running on the same connection. 100 or 128 parallel request limits are common in server implementations. Previously, the browser had a max of six connections per domain, and so used its skill and judgement to decide how best to use those connections. Now, it rarely needs to queue and can send all requests as soon as it knows about them. This can then lead to the bandwidth being “wasted” on lower priority requests while critical requests are delayed (and incidentally can also lead to swamping your backend server with more requests than it is used to!).

HTTP/2 has a complex prioritization model (too complex many say - hence why it is being reconsidered for HTTP/3!) but few servers honor that properly. This can be because their HTTP/2 implementations are not up to scratch, or because of so-called bufferbloat, where the responses are already en route before the server realizes there is a higher priority request. Due to the varying nature of servers, TCP stacks, and locations, it is difficult to measure this for most sites, but with CDNs this should be more consistent.

Patrick Meenan created an example test page, which deliberately tries to download a load of low priority, off-screen images, before requesting some high priority on-screen images. A good HTTP/2 server should be able to recognize this and send the high priority images shortly after requested, at the expense of the lower priority images. A poor HTTP/2 server will just respond in the request order and ignore any priority signals. Andy Davies has a page tracking the status of various CDNs for Patrick’s test. The HTTP Archive identifies when a CDN is used as part of its crawl, and merging these two datasets can tell us the percent of pages using a passing or failing CDN.

| CDN | Prioritizes Correctly? | Desktop | Mobile | Both |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not using CDN | Unknown | 57.81% | 60.41% | 59.21% |

| Cloudflare | Pass | 23.15% | 21.77% | 22.40% |

| Fail | 6.67% | 7.11% | 6.90% | |

| Amazon CloudFront | Fail | 2.83% | 2.38% | 2.59% |

| Fastly | Pass | 2.40% | 1.77% | 2.06% |

| Akamai | Pass | 1.79% | 1.50% | 1.64% |

| Unknown | 1.32% | 1.58% | 1.46% | |

| WordPress | Pass | 1.12% | 0.99% | 1.05% |

| Sucuri Firewall | Fail | 0.88% | 0.75% | 0.81% |

| Incapsula | Fail | 0.39% | 0.34% | 0.36% |

| Netlify | Fail | 0.23% | 0.15% | 0.19% |

| OVH CDN | Unknown | 0.19% | 0.18% | 0.18% |

Figure 20.14 shows that a fairly significant portion of traffic is subject to the identified issue, totaling 26.82% on desktop and 27.83% on mobile. How much of a problem this is depends on exactly how the page loads and whether high priority resources are discovered late or not for the sites affected.

Another issue is with the upgrade HTTP header being used incorrectly. Web servers can respond to requests with an upgrade HTTP header suggesting that it supports a better protocol that the client might wish to use (e.g. advertise HTTP/2 to a client only using HTTP/1.1). You might think this would be useful as a way of informing the browser a server supports HTTP/2, but since browsers only support HTTP/2 over HTTPS and since use of HTTP/2 can be negotiated through the HTTPS handshake, the use of this upgrade header for advertising HTTP/2 is pretty limited (for browsers at least).

Worse than that, is when a server sends an upgrade header in error. This could be because a backend server supporting HTTP/2 is sending the header and then an HTTP/1.1-only edge server is blindly forwarding it to the client. Apache emits the upgrade header when mod_http2 is enabled but HTTP/2 is not being used, and an nginx instance sitting in front of such an Apache instance happily forwards this header even when nginx does not support HTTP/2. This false advertising then leads to clients trying (and failing!) to use HTTP/2 as they are advised to.

108 sites use HTTP/2 while they also suggest upgrading to HTTP/2 in the upgrade header. A further 12,767 sites on desktop (15,235 on mobile) suggest upgrading an HTTP/1.1 connection delivered over HTTPS to HTTP/2 when it’s clear this was not available, or it would have been used already. These are a small minority of the 4.3 million sites crawled on desktop and 5.3 million sites crawled on mobile, but it shows that this is still an issue affecting a number of sites out there. Browsers handle this inconsistently, with Safari in particular attempting to upgrade and then getting itself in a mess and refusing to display the site at all.

All of this is before we get into the few sites that recommend upgrading to http1.0, http://1.1, or even -all,+TLSv1.3,+TLSv1.2. There are clearly some typos in web server configurations going on here!

There are further implementation issues we could look at. For example, HTTP/2 is much stricter about HTTP header names, rejecting the whole request if you respond with spaces, colons, or other invalid HTTP header names. The header names are also converted to lowercase, which catches some by surprise if their application assumes a certain capitalization. This was never guaranteed previously, as HTTP/1.1 specifically states the header names are case insensitive, but still some have depended on this. The HTTP Archive could potentially be used to identify these issues as well, though some of them will not be apparent on the home page, but we did not delve into that this year.

HTTP/3

The world does not stand still, and despite HTTP/2 not having even reached its fifth birthday, people are already seeing it as old news and getting more excited about its successor, HTTP/3. HTTP/3 builds on the concepts of HTTP/2, but moves from working over TCP connections that HTTP has always used, to a UDP-based protocol called QUIC. This allows us to fix one case where HTTP/2 is slower then HTTP/1.1, when there is high packet loss and the guaranteed nature of TCP holds up all streams and throttles back all streams. It also allows us to address some TCP and HTTPS inefficiencies, such as consolidating in one handshake for both, and supporting many ideas for TCP that have proven hard to implement in real life (TCP fast open, 0-RTT, etc.).

HTTP/3 also cleans up some overlap between TCP and HTTP/2 (e.g. flow control being implemented in both layers) but conceptually it is very similar to HTTP/2. Web developers who understand and have optimized for HTTP/2 should have to make no further changes for HTTP/3. Server operators will have more work to do, however, as the differences between TCP and QUIC are much more groundbreaking. They will make implementation harder so the rollout of HTTP/3 may take considerably longer than HTTP/2, and initially be limited to those with certain expertise in the field like CDNs.

QUIC has been implemented by Google for a number of years and it is now undergoing a similar standardization process that SPDY did on its way to HTTP/2. QUIC has ambitions beyond just HTTP, but for the moment it is the use case being worked on currently. Just as this chapter was being written, Cloudflare, Chrome, and Firefox all announced HTTP/3 support, despite the fact that HTTP/3 is still not formally complete or approved as a standard yet. This is welcome as QUIC support has been somewhat lacking outside of Google until recently, and definitely lags behind SPDY and HTTP/2 support from a similar stage of standardization.

Because HTTP/3 uses QUIC over UDP rather than TCP, it makes the discovery of HTTP/3 support a bigger challenge than HTTP/2 discovery. With HTTP/2 we can mostly use the HTTPS handshake, but as HTTP/3 is on a completely different connection, that is not an option here. HTTP/2 also used the upgrade HTTP header to inform the browser of HTTP/2 support, and although that was not that useful for HTTP/2, a similar mechanism has been put in place for QUIC that is more useful. The alternative services HTTP header (alt-svc) advertises alternative protocols that can be used on completely different connections, as opposed to alternative protocols that can be used on this connection, which is what the upgrade HTTP header is used for.

Analysis of this header shows that 7.67% of desktop sites and 8.38% of mobile sites already support QUIC, which roughly represents Google’s percentage of traffic, unsurprisingly enough, as it has been using this for a while. And 0.04% are already supporting HTTP/3. I would imagine by next year’s Web Almanac, this number will have increased significantly.

Conclusion

This analysis of the available statistics in the HTTP Archive project has shown what many of us in the HTTP community were already aware of: HTTP/2 is here and proving to be very popular. It is already the dominant protocol in terms of number of requests, but has not quite overtaken HTTP/1.1 in terms of number of sites that support it. The long tail of the internet means that it often takes an exponentially longer time to make noticeable gains on the less well-maintained sites than on the high profile, high volume sites.

We’ve also talked about how it is (still!) not easy to get HTTP/2 support in some installations. Server developers, operating system distributors, and end customers all have a part to play in pushing to make that easier. Tying software to operating systems always lengthens deployment time. In fact, one of the very reasons for QUIC is to break a similar barrier with deploying TCP changes. In many instances, there is no real reason to tie web server versions to operating systems. Apache (to use one of the more popular examples) will run with HTTP/2 support in older operating systems, but getting an up-to-date version on to the server should not require the expertise or risk it currently does. Nginx does very well here, hosting repositories for the common Linux flavors to make installation easier, and if the Apache team (or the Linux distribution vendors) do not offer something similar, then I can only see Apache’s usage continuing to shrink as it struggles to hold relevance and shake its reputation as old and slow (based on older installs) even though up-to-date versions have one of the best HTTP/2 implementations. I see that as less of an issue for IIS, since it is usually the preferred web server on the Windows side.

Other than that, HTTP/2 has been a relatively easy upgrade path, which is why it has had the strong uptake it has already seen. For the most part, it is a painless switch-on and, therefore, for most, it has turned out to be a hassle-free performance increase that requires little thought once your server supports it. The devil is in the details though (as always), and small differences between server implementations can result in better or worse HTTP/2 usage and, ultimately, end user experience. There has also been a number of bugs and even security issues, as is to be expected with any new protocol.

Ensuring you are using a strong, up-to-date, well-maintained implementation of any newish protocol like HTTP/2 will ensure you stay on top of these issues. However, that can take expertise and managing. The roll out of QUIC and HTTP/3 will likely be even more complicated and require more expertise. Perhaps this is best left to third-party service providers like CDNs who have this expertise and can give your site easy access to these features? However, even when left to the experts, this is not a sure thing (as the prioritization statistics show), but if you choose your server provider wisely and engage with them on what your priorities are, then it should be an easier implementation.

On that note it would be great if the CDNs prioritized these issues (pun definitely intended!), though I suspect with the advent of a new prioritization method in HTTP/3, many will hold tight. The next year will prove yet more interesting times in the HTTP world.