HTTP/2

Introduction

HTTP is an application layer protocol designed to transfer information between networked devices and runs on top of other layers of the network protocol stack. After HTTP/1.x was released, it took over 20 years until the first major update, HTTP/2, was made a standard in 2015.

It didn’t stop there: over the last four years, HTTP/3 and QUIC (a new latency-reducing, reliable, and secure transport protocol) have been under standards development in the IETF QUIC working group. There are actually two protocols that share the same name: “Google QUIC” (“gQUIC” for short), the original protocol that was designed and used by Google, and the newer IETF standardized version (IETF QUIC/QUIC). IETF QUIC was based on gQUIC, but has grown to be quite different in design and implementation. On October 21, 2020, draft 32 of IETF QUIC reached a significant milestone when it moved to Last Call. This is the part of the standardization process when the working group believes they are almost finished and requests a final review from the wider IETF community.

This chapter reviews the current state of HTTP/2 and gQUIC deployment. It explores how well some of the newer features of the protocol, such as prioritization and server push, have been adopted. We then look at the motivations for HTTP/3, describe the major differences between the protocol versions, and discuss the potential challenges in upgrading to a UDP-based transport protocol with QUIC.

HTTP/1.0 to HTTP/2

As the HTTP protocol has evolved, the semantics of HTTP have stayed the same; there have been no changes to the HTTP methods (such as GET or POST), status codes (200, or the dreaded 404), URIs, or header fields. Where the HTTP protocol has changed, the differences have been the wire-encoding and the use of features of the underlying transport.

HTTP/1.0, published in 1996, defined the text-based application protocol, allowing clients and servers to exchange messages in order to request resources. A new TCP connection was required for each request/response, which introduced overhead. TCP connections use a congestion control algorithm to maximize how much data can be in-flight. This process takes time for each new connection. This “slow-start” means that not all the available bandwidth is used immediately.

In 1997, HTTP/1.1 was introduced to allow TCP connection reuse by adding “keep-alives”, aimed at reducing the total cost of connection start-ups. Over time, increasing website performance expectations led to the need for concurrency of requests. HTTP/1.1 could only request another resource after the previous response had completed. Therefore, additional TCP connections had to be established, reducing the impact of the keep-alive connections and further increasing overhead.

HTTP/2, published in 2015, is a binary-based protocol that introduced the concept of bidirectional streams between client and server. Using these streams, a browser can make optimal use of a single TCP connection to multiplex multiple HTTP requests/responses concurrently. HTTP/2 also introduced a prioritization scheme to steer this multiplexing; clients can signal a request priority that allows more important resources to be sent ahead of others.

HTTP/2 Adoption

The data used in this chapter is sourced from the HTTP Archive and tests over seven million websites with a Chrome browser. As with other chapters, the analysis is split by mobile and desktop websites. When the results between desktop and mobile are similar, statistics are presented from the mobile dataset. You can find more details on the Methodology page. When reviewing this data, please bear in mind that each website will receive equal weight regardless of the number of requests. We suggest you think of this more as investigating the trends across a broad range of active websites.

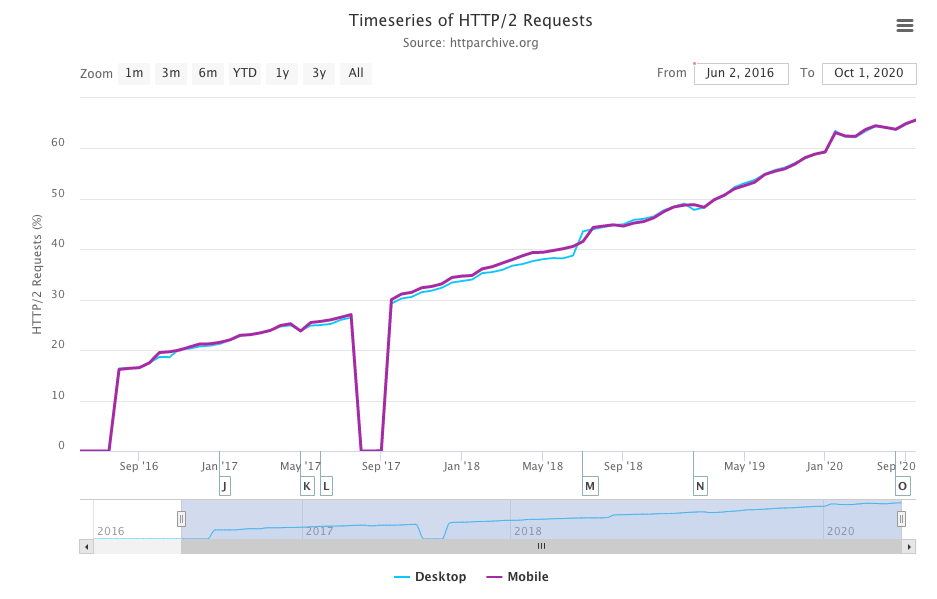

Last year’s analysis of HTTP Archive data showed that HTTP/2 was used for over 50% of requests and, as can be seen, linear growth has continued in 2020; now in excess of 60% of requests are served over HTTP/2.

When comparing Figure 22.3 with last year’s results, there has been a 10% increase in HTTP/2 requests and a corresponding 10% decrease in HTTP/1.x requests. This is the first year that gQUIC can be seen in the dataset.

| Protocol | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

| HTTP/1.1 | **34.47% | 34.11% |

| HTTP/2 | 63.70% | 63.80% |

| gQUIC | 1.72% | 1.71% |

When reviewing the total number of website requests, there will be a bias towards common third-party domains. To get a better understanding of the HTTP/2 adoption by server install, we will look instead at the protocol used to serve the HTML from the home page of a site.

Last year around 37% of home pages were served over HTTP/2 and 63% over HTTP/1. This year, combining mobile and desktop, it is a roughly equal split, with slightly more desktop sites being served over HTTP/2 for the first time, as shown in Figure 22.4.

| Protocol | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

| HTTP/1.0 | 0.06% | 0.05% |

| HTTP/1.1 | 49.22% | 50.05% |

| HTTP/2 | 49.97% | 49.28% |

gQUIC is not seen in the home page data for two reasons. To measure a website over gQUIC, the HTTP Archive crawl would have to perform protocol negotiation via the alternative services header and then use this endpoint to load the site over gQUIC. This was not supported this year, but expect it to be available in next year’s Web Almanac. Also, gQUIC is predominantly used for third-party Google tools rather than serving home pages.

The drive to increase security and privacy on the web has seen requests over TLS increase by over 150% in the last 4 years. Today, over 86% of all requests on mobile and desktop are encrypted. Looking only at home pages, the numbers are still an impressive 78.1% of desktop and 74.7% of mobile. This is important because HTTP/2 is only supported by browsers over TLS. The proportion served over HTTP/2, as shown in Figure 22.5, has also increased by 10 percentage points from last year, from 55% to 65%.

| Protocol | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

| HTTP/1.1 | 36.05% | 34.04% |

| HTTP/2 | 63.95% | 65.96% |

With over 60% of websites being served over HTTP/2 or gQUIC, let’s look a little deeper into the pattern of protocol distribution for all requests made across individual sites.

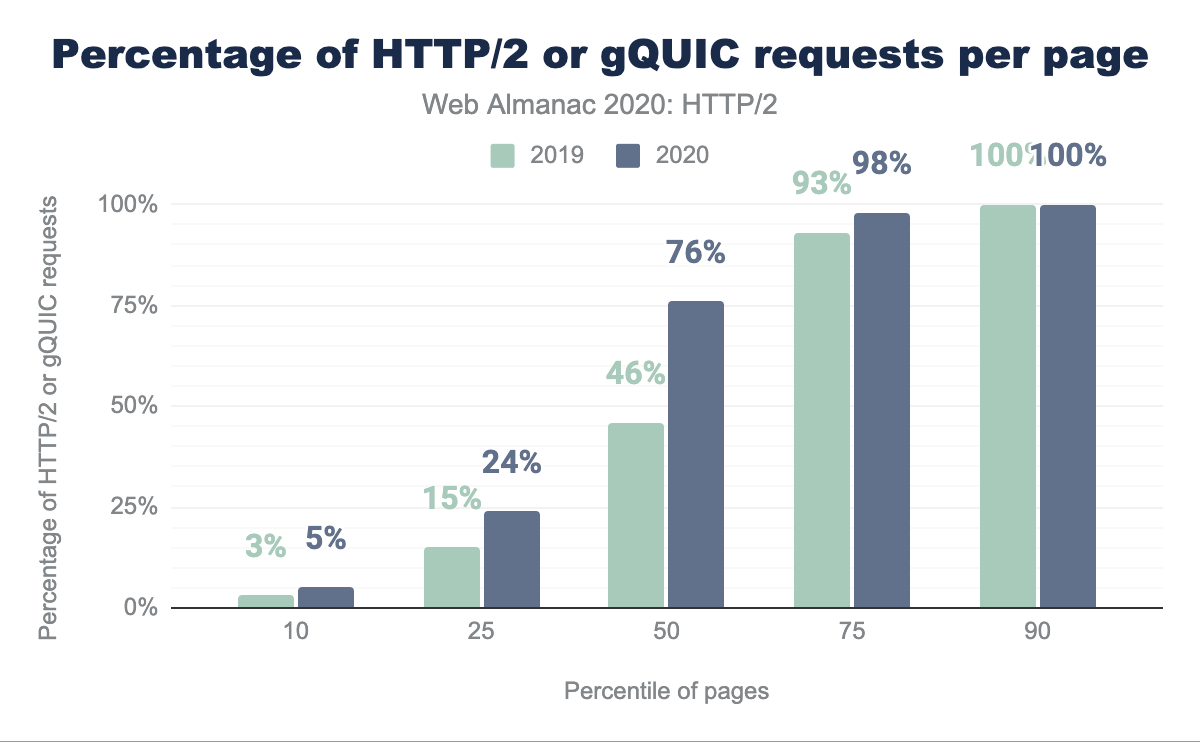

Figure 22.6 compares how much HTTP/2 or gQUIC is used on a website between this year and last year. The most noticeable change is that over half of sites now have 75% or more of their requests served over HTTP/2 or gQUIC compared to 46% last year. Less than 7% of sites make no HTTP/2 or gQUIC requests, while (only) 10% of sites are entirely HTTP/2 or gQUIC requests.

What about the breakdown of the page itself? We typically talk about the difference between first-party and third-party content. Third-party is defined as content not within the direct control of the site owner, providing functionality such as advertising, marketing or analytics. The definition of known third parties is taken from the third party web repository.

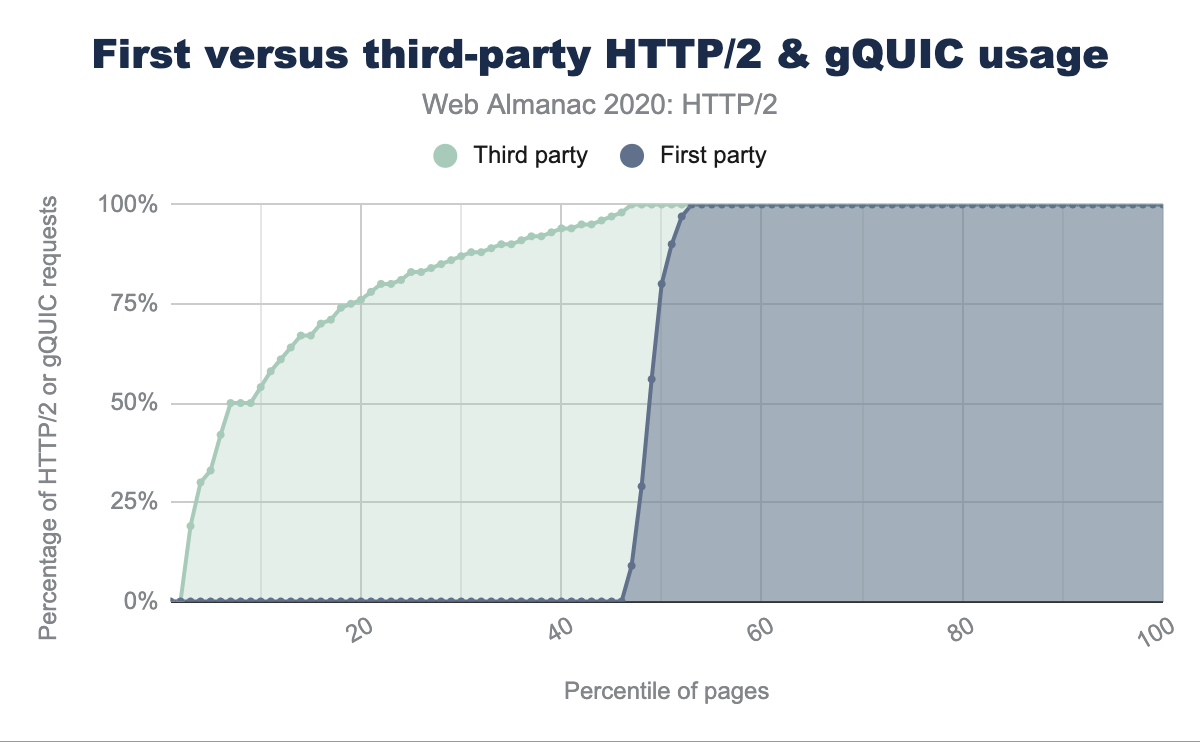

Figure 22.7 orders every website by the fraction of HTTP/2 requests for known third parties or first party requests compared to other requests. There is a noticeable difference as over 40% of all sites have no first-party HTTP/2 or gQUIC requests at all. By contrast, even the lowest 5% of pages have 30% of third-party content served over HTTP/2. This indicates that a large part of HTTP/2’s broad adoption is driven by the third parties.

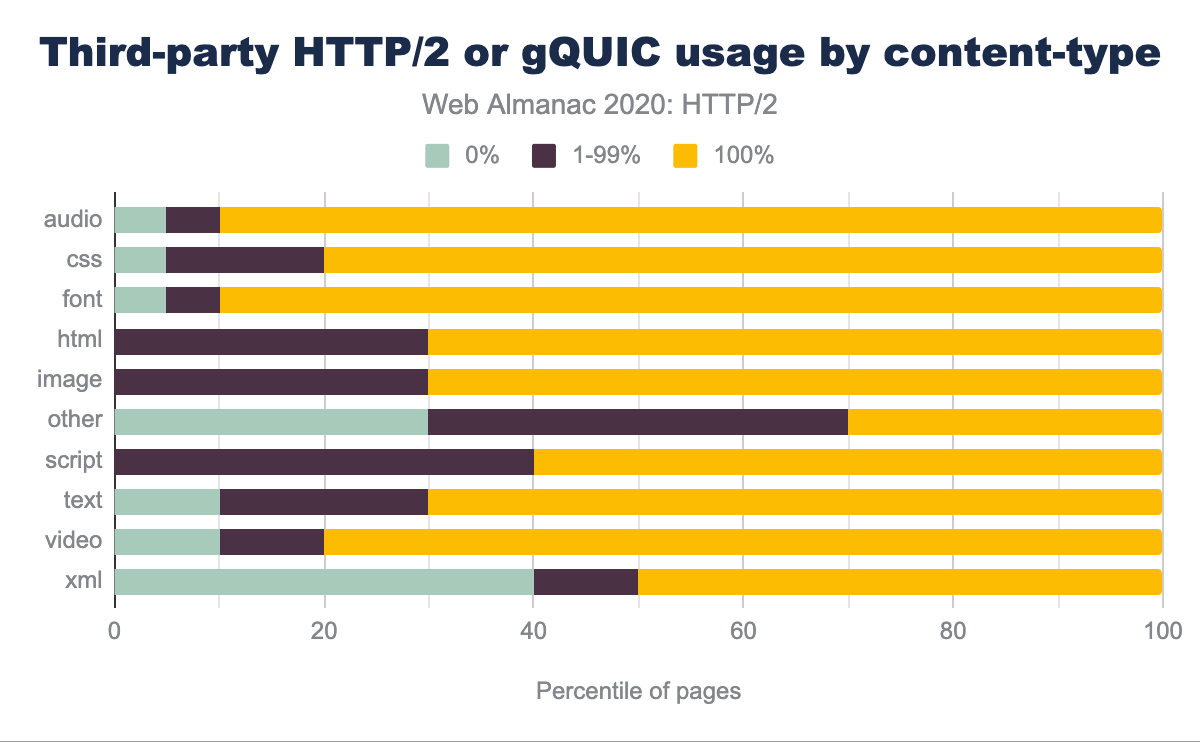

Is there any difference in which content-types are served over HTTP/2 or gQUIC? Figure 22.8 shows, for example, that 90% of websites serve 100% of third party fonts and audio over HTTP/2 or gQUIC, only 5% over HTTP/1.1 and 5% are a mix. The majority of third-party assets are either scripts or images, and are solely served over HTTP/2 or gQUIC on 60% and 70% of websites respectively.

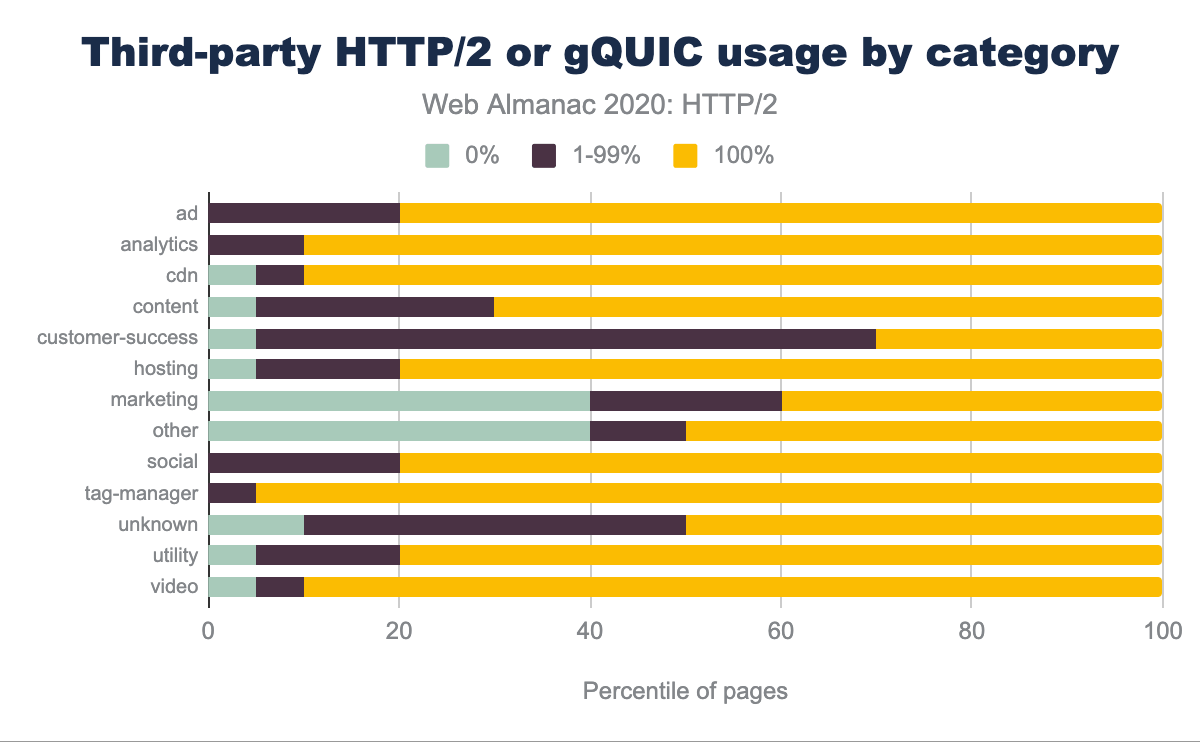

Ads, analytics, content delivery network (CDN) resources, and tag-managers are predominantly served over HTTP/2 or gQUIC as shown in Figure 22.9. Customer-success and marketing content is more likely to be served over HTTP/1.

Server support

Browser auto-update mechanisms are a driving factor for client-side adoption of new web standards. It’s estimated that over 97% of global users support HTTP/2, up slightly from 95% measured last year.

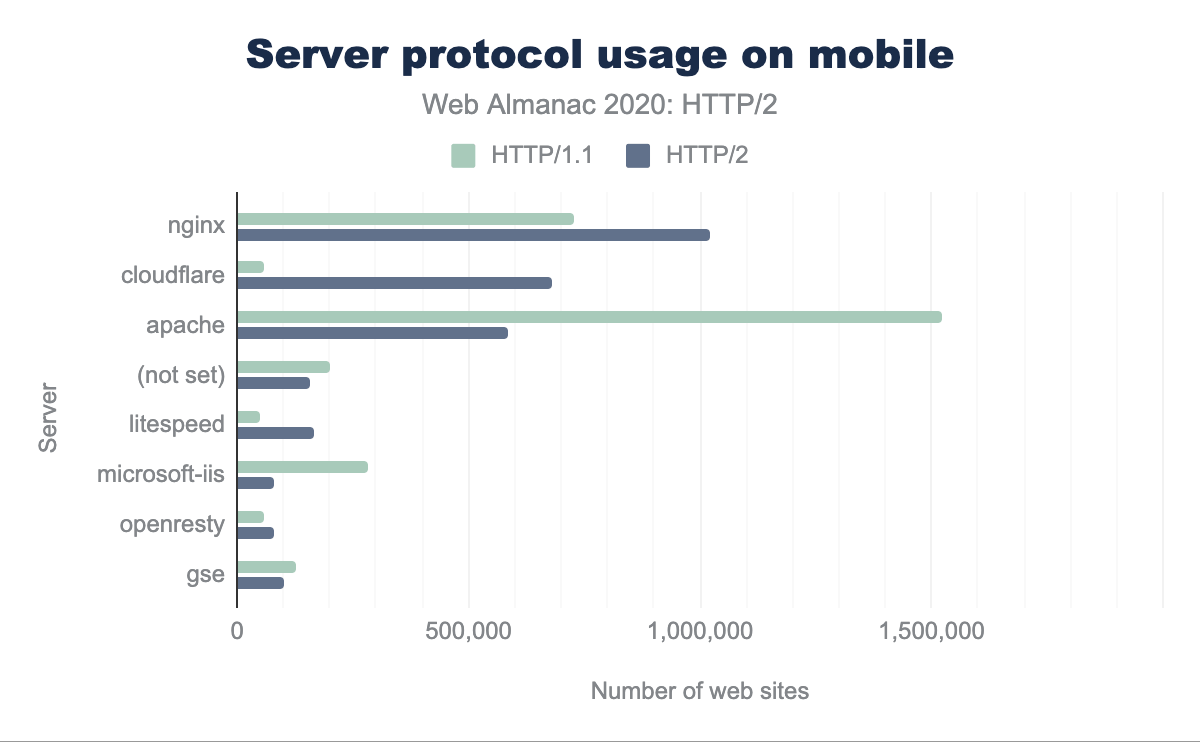

Unfortunately, the upgrade path for servers is more difficult, especially with the requirement to support TLS. For mobile and desktop, we can see from Figure 22.10, that the majority of HTTP/2 sites are served by nginx, Cloudflare, and Apache. Almost half of the HTTP/1.1 sites are served by Apache.

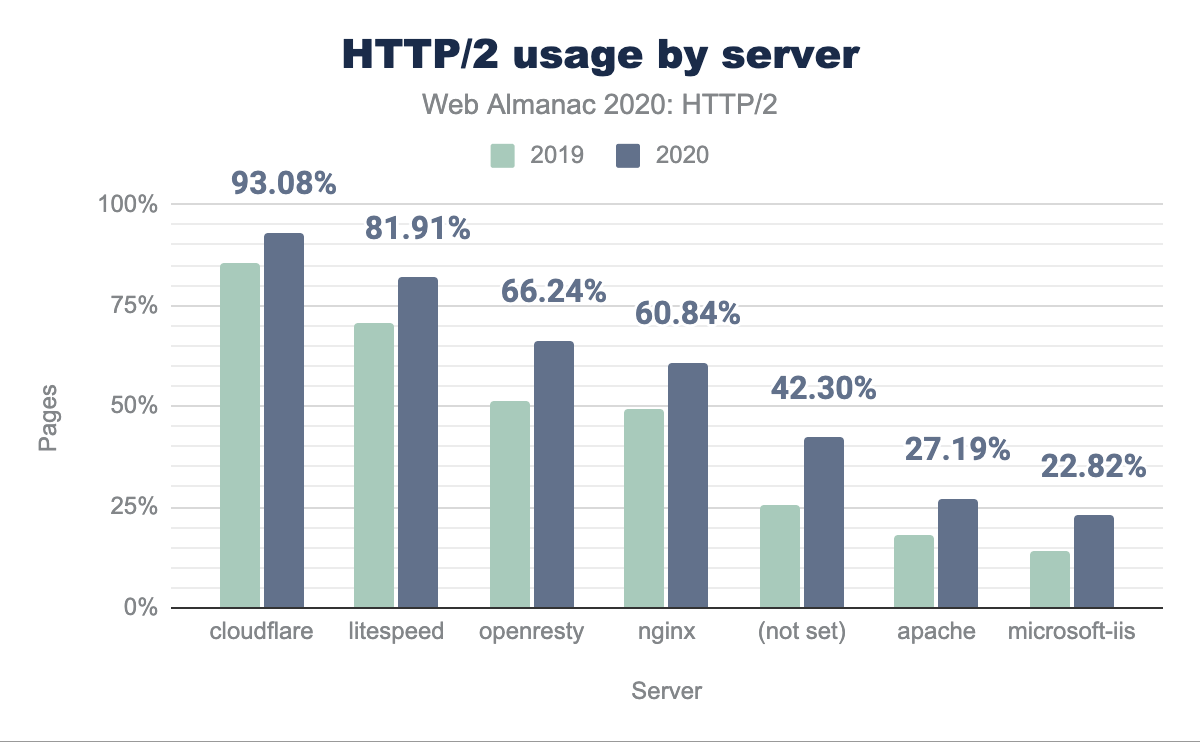

How has HTTP/2 adoption changed in the last year for each server? Figure 22.11 shows a general HTTP/2 adoption increase of around 10% across all servers since last year. Apache and IIS are still under 25% HTTP/2. This suggests that either new servers tend to be nginx or it is seen as too difficult or not worthwhile to upgrade Apache or IIS to HTTP/2 and/or TLS.

A long-term recommendation to improve website performance has been to use a CDN. The benefit is a reduction in latency by both serving content and terminating connections closer to the end user. This helps mitigate the rapid evolution in protocol deployment and the additional complexities in tuning servers and operating systems (see the Prioritization section for more details). To utilize the new protocols effectively, using a CDN can be seen as the recommended approach.

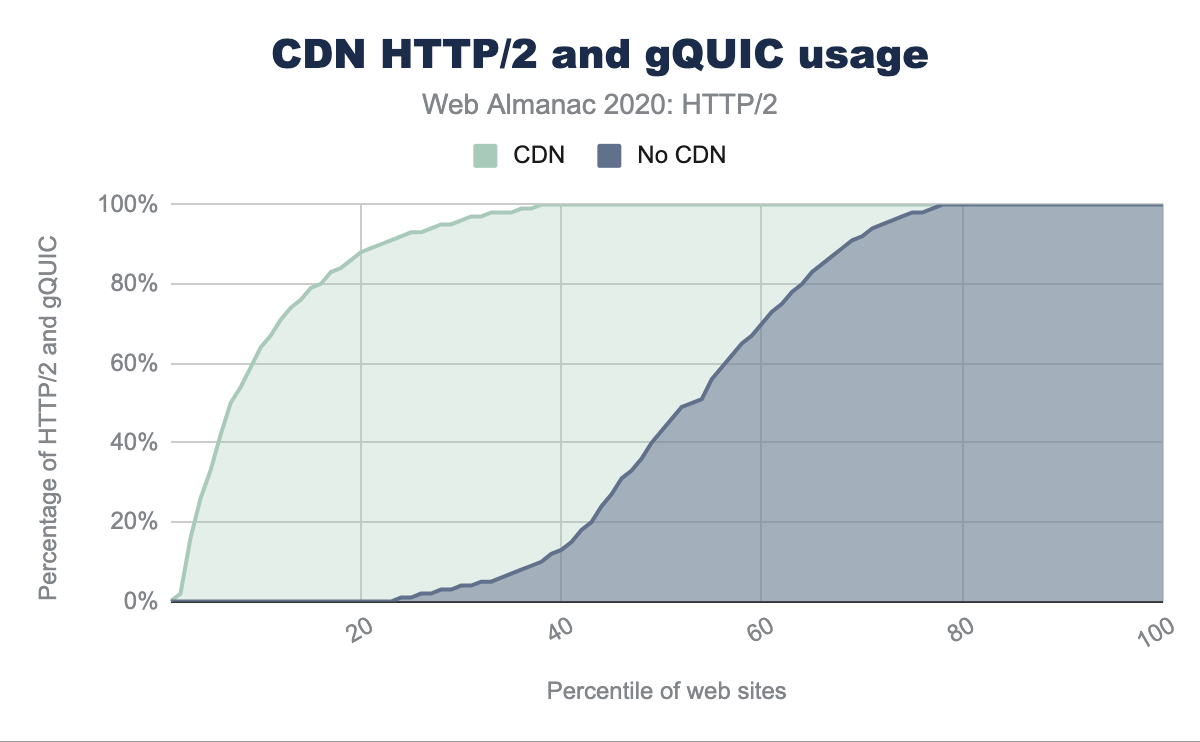

CDNs can be classed in two broad categories: those that serve the home page and/or asset subdomains, and those that are mainly used to serve third-party content. Examples of the first category are the larger generic CDNs (such as Cloudflare, Akamai, or Fastly) and the more specific (such as WordPress or Netlify). Looking at the difference in HTTP/2 adoption rates for home pages served with or without a CDN, we see:

- 80% of mobile home pages are served over HTTP/2 if a CDN is used

- 30% of mobile home pages are served over HTTP/2 if a CDN is not used

Figure 22.12 shows the more specific and the modern CDNs serve a higher proportion of traffic over HTTP/2.

| HTTP/2 (%) | CDN |

|---|---|

| 100% | Bison Grid, CDNsun, LeaseWeb CDN, NYI FTW, QUIC.cloud, Roast.io, Sirv CDN, Twitter, Zycada Networks |

| 90 - 99% | Automattic, Azion, BitGravity, Facebook, KeyCDN, Microsoft Azure, NGENIX, Netlify, Yahoo, section.io, Airee, BunnyCDN, Cloudflare, GoCache, NetDNA, SFR, Sucuri Firewall |

| 70 - 89% | Amazon CloudFront, BelugaCDN, CDN, CDN77, Erstream, Fastly, Highwinds, OVH CDN, Yottaa, Edgecast, Myra Security CDN, StackPath, XLabs Security |

| 20 - 69% | Akamai, Aryaka, Google, Limelight, Rackspace, Incapsula, Level 3, Medianova, OnApp, Singular CDN, Vercel, Cachefly, Cedexis, Reflected Networks, Universal CDN, Yunjiasu, CDNetworks |

| < 20% | Rocket CDN, BO.LT, ChinaCache, KINX CDN, Zenedge, ChinaNetCenter |

Types of content in the second category are typically shared resources (JavaScript or font CDNs), advertisements, or analytics. In all these cases, using a CDN will improve the performance and offload for the various SaaS solutions.

In Figure 22.13 we can see the stark difference in HTTP/2 and gQUIC adoption when a website is using a CDN. 70% of pages use HTTP/2 for all third-party requests when a CDN is used. Without a CDN, only 25% of pages use HTTP/2 for all third-party requests.

HTTP/2 impact

Measuring the impact of how a protocol is performing is difficult with the current HTTP Archive approach. It would be really fascinating to be able to quantify the impact of concurrent connections, the effect of packet loss, and different congestion control mechanisms. To really compare performance, each website would have to be crawled over each protocol over different network conditions. What we can do instead is to look into the impact on the number of connections a website uses.

Reducing connections

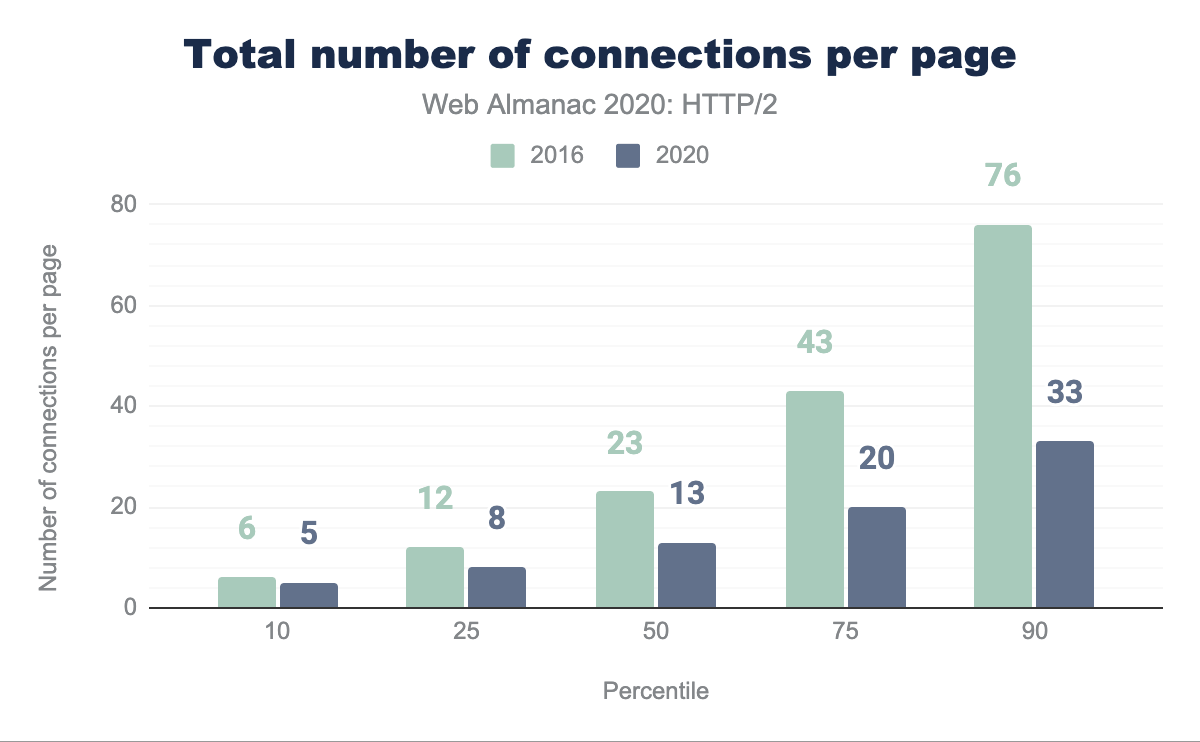

As discussed earlier, HTTP/1.1 only allows a single request at a time over a TCP connection. Most browsers get around this by allowing six parallel connections per host. The major improvement with HTTP/2 is that multiple requests can be multiplexed over a single TCP connection. This should reduce the total number of connections—and the associated time and resources—required to load a page.

Figure 22.15 shows how the number of TCP connections per page has reduced in 2020 compared with 2016. Half of all websites now use 13 or fewer TCP connections in 2020 compared with 23 connections in 2016; a 44% decrease. In the same time period the median number of requests has only dropped from 74 to 73. The median number of requests per TCP connection has increased from 3.2 to 5.6.

TCP was designed to maintain an average data flow that is both efficient and fair. Imagine a flow control process where each flow both exerts pressure on and is responsive to all other flows, to provide a fair share of the network. In a fair protocol, every TCP session does not crowd out any other session and over time will take 1/N of the path capacity.

The majority of websites still open over 15 TCP connections. In HTTP/1.1, the six connections a browser could open to a domain can over time claim six times as much bandwidth as a single HTTP/2 connection. Over low capacity networks, this can slow down the delivery of content from the primary asset domains as the number of contending connections increases and takes bandwidth away from the important requests. This favors websites with a small number of third-party domains.

HTTP/2 does allow for connection reuse across different, but related domains. For a TLS resource, it requires a certificate that is valid for the host in the URI. This can be used to reduce the number of connections required for domains under the control of the site author.

Prioritization

As HTTP/2 responses can be split into many individual frames, and as frames from multiple streams can be multiplexed, the order in which the frames are interleaved and delivered by the server becomes a critical performance consideration. A typical website consists of many different types of resources: the visible content (HTML, CSS, images), the application logic (JavaScript), ads, analytics for tracking site usage, and marketing tracking beacons. With knowledge of how a browser works, an optimal ordering of the resources can be defined that will result in the fastest user experience. The difference between optimal and non-optimal can be significant—as much as a 50% performance improvement or more!

HTTP/2 introduced the concept of prioritization to help the client communicate to the server how it thinks the multiplexing should be done. Every stream is assigned a weight (how much of the available bandwidth the stream should be allocated) and possibly a parent (another stream which should be delivered first). With the flexibility of HTTP/2’s prioritization model, it is not altogether surprising that all of the current browser engines implemented different prioritization strategies, none of which are optimal.

There are also problems on the server side, leading to many servers implementing prioritization either poorly or not at all. In the case of HTTP/1.x, tuning the server-side send buffers to be as big as possible has no downside, other than the increase in memory use (trading off memory for CPU), and is an effective way to increase the throughput of a web server. This is not true for HTTP/2, as data in the TCP send buffer cannot be re-prioritized if a request for a new, more important resource comes in. For an HTTP/2 server, the optimal send buffer size is thus the minimum amount of data required to fully utilize the available bandwidth. This allows the server to respond immediately if a higher-priority request is received.

This problem of large buffers messing with (re-)prioritization also exists in the network, where it goes by the name “bufferbloat”. Network equipment would rather buffer packets than drop them when there’s a short burst. However, if the server sends more data than the path to the client can consume, these buffers fill to capacity. These bytes already “stored” on the network limit the server’s ability to send a higher-priority response earlier, just as a large send buffer does. To minimize the amount of data held in buffers, a recent congestion control algorithm such as BBR should be used.

This test suite maintained by Andy Davies measures and reports how various CDN and cloud hosting services perform. The bad news is that only 9 of the 36 services prioritize correctly. Figure 22.16 shows that for sites using a CDN, around 31.7% do not prioritize correctly. This is up from 26.82% last year, mainly due to the increase in Google CDN usage. Rather than relying on the browser-sent priorities, there are some servers that implement a server side prioritization scheme instead, improving upon the browser’s hints with additional logic.

| CDN | Prioritize correctly |

Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not using CDN | Unknown | 59.47% | 60.85% |

| Cloudflare | Pass | 22.03% | 21.32% |

| Fail | 8.26% | 8.94% | |

| Amazon CloudFront | Fail | 2.64% | 2.27% |

| Fastly | Pass | 2.34% | 1.78% |

| Akamai | Pass | 1.31% | 1.19% |

| Automattic | Pass | 0.93% | 1.05% |

| Sucuri Firewall | Fail | 0.77% | 0.63% |

| Incapsula | Fail | 0.42% | 0.34% |

| Netlify | Fail | 0.27% | 0.20% |

For non-CDN usage, we expect the number of servers that correctly apply HTTP/2 prioritization to be considerably smaller. For example, NodeJS’s HTTP/2 implementation does not support prioritization.

Goodbye server push?

Server push was one of the additional features of HTTP/2 that caused some confusion and complexity to implement in practice. Push seeks to avoid waiting for a browser/client to download a HTML page, parse that page, and only then discover that it requires additional resources (such as a stylesheet), which in turn have to be fetched and parsed to discover even more dependencies (such as fonts). All that work and round trips takes time. With server push, in theory, the server can just send multiple responses at once, avoiding the extra round trips.

Unfortunately, with TCP congestion control in play, the data transfer starts off so slowly that not all the assets can be pushed until multiple round trips have increased the transfer rate sufficiently. There are also implementation differences between browsers as the client processing model had not been fully agreed. For example, each browser has a different implementation of a push cache.

Another issue is that the server is not aware of resources the browser has already cached. When a server tries to push something that is unwanted, the client can send a RST_STREAM frame, but by the time this has happened, the server may well have already sent all the data. This wastes bandwidth and the server has lost the opportunity of immediately sending something that the browser actually did require. There were proposals to allow clients to inform the server of their cache status, but these suffered from privacy concerns.

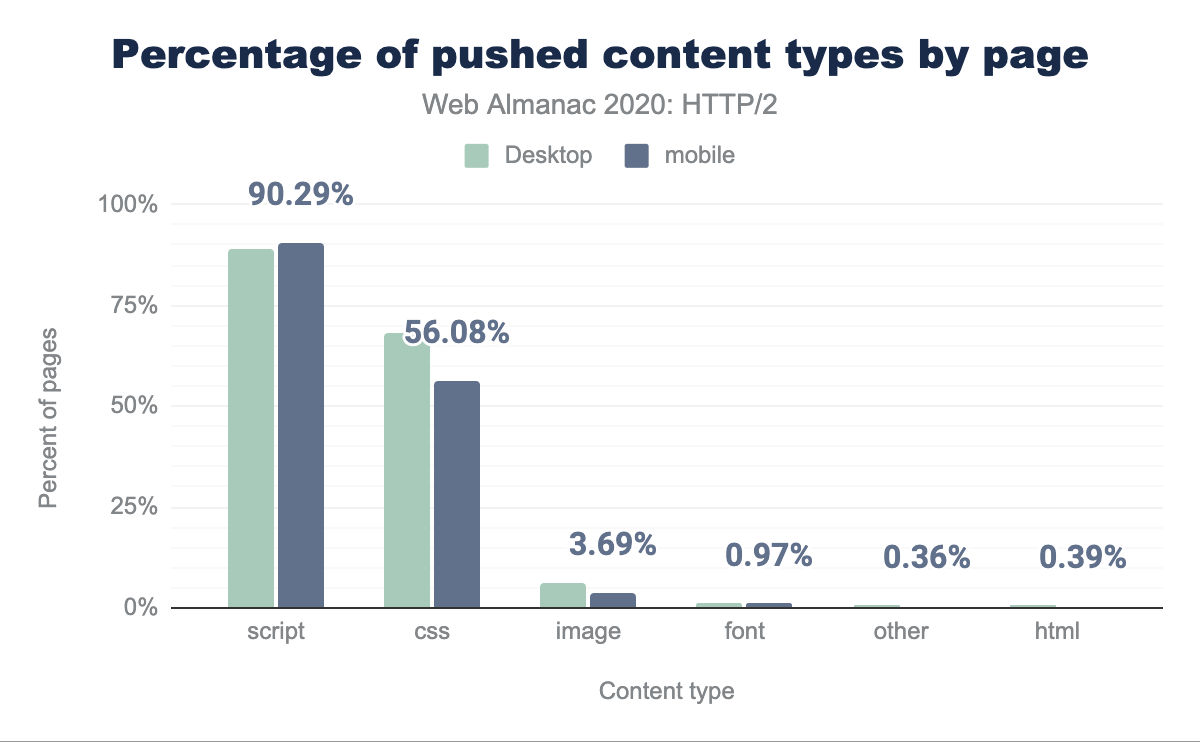

As can be seen from the Figure 20.17 below, a very small percentage of sites use server push.

| Client | HTTP/2 pages | HTTP/2 (%) | gQUIC pages | gQUIC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desktop | 44,257 | 0.85% | 204 | 0.04% |

| Mobile | 62,849 | 1.06% | 326 | 0.06% |

Looking further at the distributions for pushed assets in Figures 22.18 and 22.19, half of the sites push 4 or fewer resources with a total size of 140 KB on desktop and 3 or fewer resources with a size of 184 KB on mobile. For gQUIC, desktop is 7 or fewer and mobile 2. The worst offending page pushes 41 assets over gQUIC on desktop.

| Percentile | HTTP/2 | Size (KB) | gQUIC | Size (KB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 1 | 3.95 | 1 | 15.83 |

| 25 | 2 | 36.32 | 3 | 35.93 |

| 50 | 4 | 139.58 | 7 | 111.96 |

| 75 | 8 | 346.70 | 21 | 203.59 |

| 90 | 17 | 440.08 | 41 | 390.91 |

| Percentile | HTTP/2 | Size (KB) | gQUIC | Size (KB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 1 | 15.48 | 1 | 0.06 |

| 25 | 1 | 36.34 | 1 | 0.06 |

| 50 | 3 | 183.83 | 2 | 24.06 |

| 75 | 10 | 225.41 | 5 | 204.65 |

| 90 | 12 | 351.05 | 18 | 453.57 |

Looking at the frequency of push by content type in Figure 22.20, we see 90% of pages push scripts and 56% push CSS. This makes sense, as these can be small files typically on the critical path to render a page.

Given the low adoption, and after measuring how few of the pushed resources are actually useful (that is, they match a request that is not already cached), Google has announced the intent to remove push support from Chrome for both HTTP/2 and gQUIC. Chrome has also not implemented push for HTTP/3.

Despite all these problems, there are circumstances where server push can provide an improvement. The ideal use case is to be able to send a push promise much earlier than the HTML response itself. A scenario where this can benefit is when a CDN is in use. The “dead time” between the CDN receiving the request and receiving a response from the origin can be used intelligently to warm up the TCP connection and push assets already cached at the CDN.

There was however no standardized method for how to signal to a CDN edge server that an asset should be pushed. Implementations instead reused the preload HTTP link header to indicate this. This simple approach appears elegant, but it does not utilize the dead time before the HTML is generated unless the headers are sent before the actual content is ready. It triggers the edge to push resources as the HTML is received at the edge, which will contend with the delivery of the HTML.

An alternative proposal being tested is RFC 8297, which defines an informative 103 (Early Hints) response. This permits headers to be sent immediately, without having to wait for the server to generate the full response headers. This can be used by an origin to suggest pushed resources to a CDN, or by a CDN to alert the client to resources that need to be fetched. However, at present, support for this from both a client and server perspective is very low, but growing.

Getting to a better protocol

Let’s say a client and server support both HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2. How do they choose which one to use? The most common method is TLS Application Layer Protocol Negotiation (ALPN), in which clients send a list of protocols they support to the server, which picks the one it prefers to use for that connection. Because the browser needs to negotiate the TLS parameters as part of setting up an HTTPS connection, it can also negotiate the HTTP version at the same time. Since both HTTP/2 and HTTP/1.1 can be served from the same TCP port (443), browsers don’t need to make this selection before opening a connection.

This doesn’t work if the protocols aren’t on the same port, use a different transport protocol (TCP versus QUIC), or if you’re not using TLS. For those scenarios, you start with whatever is available on the first port you connect to, then discover other options. HTTP defines two mechanisms to change protocols for an origin after connecting: Upgrade and Alt-Svc.

Upgrade

The Upgrade header has been part of HTTP for a long time. In HTTP/1.x, Upgrade allows a client to make a request using one protocol, but indicate its support for another protocol (like HTTP/2). If the server also supports the offered protocol, it responds with a status 101 (Switching Protocols) and proceeds to answer the request in the new protocol. If not, the server answers the request in HTTP/1.x. Servers can advertise their support of a different protocol using an Upgrade header on a response.

The most common application of Upgrade is WebSockets. HTTP/2 also defines an Upgrade path, for use with its unencrypted cleartext mode. There is no support for this capability in web browsers, however. Therefore, it’s not surprising that less than 3% of cleartext HTTP/1.1 requests in our dataset received an Upgrade header in the response. A very small number of requests using TLS (0.0011% of HTTP/2, 0.064% of HTTP/1.1) also received Upgrade headers in response; these are likely cleartext HTTP/1.1 servers behind intermediaries which speak HTTP/2 and/or terminate TLS, but don’t properly remove Upgrade headers.

Alternative Services

Alternative Services (Alt-Svc) enables an HTTP origin to indicate other endpoints which serve the same content, possibly over different protocols. Although uncommon, HTTP/2 might be located at a different port or different host from a site’s HTTP/1.1 service. More importantly, since HTTP/3 uses QUIC (hence UDP) where prior versions of HTTP use TCP, HTTP/3 will always be at a different endpoint from the HTTP/1.x and HTTP/2 service.

When using Alt-Svc, a client makes requests to the origin as normal. However, if the server includes a header or sends a frame containing a list of alternatives, the client can make a new connection to the other endpoint and use it for future requests to that origin.

Unsurprisingly, Alt-Svc usage is found almost entirely from services using advanced HTTP versions: 12.0% of HTTP/2 requests and 60.1% of gQUIC requests received an Alt-Svc header in response, as compared to 0.055% of HTTP/1.x requests. Note that our methodology here only captures Alt-Svc headers, not ALTSVC frames in HTTP/2, so reality might be slightly understated.

While Alt-Svc can point to an entirely different host, support for this capability varies among browsers. Only 4.71% of Alt-Svc headers advertised an endpoint on a different hostname; these were almost universally (99.5%) advertising gQUIC and HTTP/3 support on Google Ads. Google Chrome ignores cross-host Alt-Svc advertisements for HTTP/2, so many of the other instances would have been ignored.

Given the rarity of support for cross-host HTTP/2, it’s not surprising that there were virtually no (0.007%) advertisements for HTTP/2 endpoints using Alt-Svc. Alt-Svc was typically used to indicate support for HTTP/3 (74.6% of Alt-Svc headers) or gQUIC (38.7% of Alt-Svc headers).

Looking toward the future: HTTP/3

HTTP/2 is a powerful protocol, which has found considerable adoption in just a few years. However, HTTP/3 over QUIC is already peeking around the corner! Over four years in the making, this next version of HTTP is almost standardized at the IETF (expected in the first half of 2021). At this time, there are already many QUIC and HTTP/3 implementations available, both for servers and browsers. While these are relatively mature, they can still be said to be in an experimental state.

This is reflected by the usage numbers in the HTTP Archive data, where no HTTP/3 requests were identified at all. This might seem a bit strange, since Cloudflare has had experimental HTTP/3 support for some time, as have Google and Facebook. This is mainly because Chrome hadn’t enabled the protocol by default when the data was collected.

However, even the numbers for the older gQUIC are relatively modest, accounting for less than 2% of requests overall. This is expected, since gQUIC was mostly deployed by Google and Akamai; other parties were waiting for IETF QUIC. As such, gQUIC is expected to be replaced entirely by HTTP/3 soon.

It’s important to note that this low adoption only reflects gQUIC and HTTP/3 usage for loading Web pages. For several years already, Facebook has had a much more extensive deployment of IETF QUIC and HTTP/3 for loading data inside of its native applications. QUIC and HTTP/3 already make up over 75% of their total internet traffic. It is clear that HTTP/3 is only just getting started!

Now you might wonder: if not everyone is already using HTTP/2, why would we need HTTP/3 so soon? What benefits can we expect in practice? Let’s take a closer look at its internal mechanisms.

QUIC and HTTP/3

Past attempts to deploy new transport protocols on the internet have proven difficult, for example Stream Control Transmission Protocol (SCTP). QUIC is a new transport protocol that runs on top of UDP. It provides similar features to TCP, such as reliable in-order delivery and congestion control to prevent flooding the network.

As discussed in the HTTP/1.0 to HTTP/2 section, HTTP/2 multiplexes multiple different streams on top of one connection. TCP itself is woefully unaware of this fact, leading to inefficiencies or performance impact when packet loss or delays occur. More details on this problem, known as head-of-line blocking (HOL blocking), can be found here.

QUIC solves the HOL blocking problem by bringing HTTP/2’s streams down into the transport layer and performing per-stream loss detection and retransmission. So then we just put HTTP/2 over QUIC, right? Well, we’ve already mentioned some of the difficulties arising from having flow control in TCP and HTTP/2. Running two separate and competing streaming systems on top of each other would be an additional problem. Furthermore, because the QUIC streams are independent, it would mess with the strict ordering requirements HTTP/2 requires for several of its systems.

In the end, it was deemed easier to define a new HTTP version that uses QUIC directly and thus, HTTP/3 was born. Its high-level features are very similar to those we know from HTTP/2, but internal implementation mechanisms are quite different. HPACK header compression is replaced with QPACK, which allows manual tuning of the compression efficiency versus HOL blocking risk tradeoff, and the prioritization system is being replaced by a simpler one. The latter could also be back-ported to HTTP/2, possibly helping resolve the prioritization issues discussed earlier in this article. HTTP/3 continues to provide a server push mechanism, but Chrome, for example, does not implement it.

Another benefit of QUIC is that it is able to migrate connections and keep them alive even when the underlying network changes. A typical example is the so-called “parking lot problem”. Imagine your smartphone is connected to the workplace Wi-Fi network and you’ve just started downloading a large file. As you leave Wi-Fi range, your phone automatically switches to the fancy new 5G cellular network. With plain old TCP, the connection would break and cause an interruption. But QUIC is smarter; it uses a connection ID, which is more robust to network changes, and provides an active connection migration feature for clients to switch without interruption.

Finally, TLS is already used to protect HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2. QUIC, however, has a deep integration of TLS 1.3, protecting both HTTP/3 data and QUIC packet metadata, such as packet numbers. Using TLS in this way improves end-user privacy and security and makes continued protocol evolution easier. Combining the transport and cryptographic handshakes means that connection setup takes just a single RTT, compared to TCP’s minimum of two and worst case of four. In some cases, QUIC can even go one step further and send HTTP data along with its very first message, which is called 0-RTT. These fast connection setup times are expected to really help HTTP/3 outperform HTTP/2.

So, will HTTP/3 help?

On the surface, HTTP/3 is really not all that different from HTTP/2. It doesn’t add any major features, but mainly changes how the existing ones work under the surface. The real improvements come from QUIC, which offers faster connection setups, increased robustness, and resilience to packet loss. As such, HTTP/3 is expected to do better than HTTP/2 on worse networks, while offering very similar performance on faster systems. However, that is if the web community can get HTTP/3 working, which can be challenging in practice.

Deploying and discovering HTTP/3

Since QUIC and HTTP/3 run over UDP, things aren’t as simple as with HTTP/1.1 or HTTP/2. Typically, an HTTP/3 client has to first discover that QUIC is available at the server. The recommended method for this is HTTP Alternative Services . On its first visit to a website, a client connects to a server using TCP. It then discovers via Alt-Svc that HTTP/3 is available, and can set up a new QUIC connection. The Alt-Svc entry can be cached, allowing subsequent visits to avoid the TCP step, but the entry will eventually become stale and need revalidation. This likely will have to be done for each domain separately, which will probably lead to most page loads using a mix of HTTP/1.1, HTTP/2, and HTTP/3.

However, even if it is known that a server supports QUIC and HTTP/3, the network in between might block it. UDP traffic is commonly used in DDoS attacks and blocked by default in for example many company networks. While exceptions could be made for QUIC, its encryption makes it difficult for firewalls to assess the traffic. There are potential solutions to these issues, but in the meantime it is expected that QUIC is most likely to succeed on well-known ports like 443. And it is entirely possible that it is blocked QUIC altogether. In practice, clients will likely use sophisticated mechanisms to fall back to TCP if QUIC fails. One option is to “race” both a TCP and QUIC connection and use the one that completes first.

There is ongoing work to define ways to discover HTTP/3 without needing the TCP step. This should be considered an optimization, though, as the UDP blocking issues are likely to mean that TCP-based HTTP sticks around. The HTTPS DNS record is similar to HTTP Alternative Services and some CDNs are already experimenting with these records. In the long run, when most servers offer HTTP/3, browsers might switch to attempting that by default; that will take a long time.

| HTTP/1.x | HTTP/2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLS version | Desktop | Mobile | Desktop | Mobile |

| unknown | 4.06% | 4.03% | 5.05% | 7.28% |

| TLS 1.2 | 26.56% | 24.75% | 23.12% | 23.14% |

| TLS 1.3 | 5.25% | 5.11% | 35.78% | 35.54% |

QUIC is dependent on TLS 1.3, which is used for around 41% of requests, as shown in Figure 22.21. That leaves 59% of requests that will need to update their TLS stack to support HTTP/3.

Is HTTP/3 ready yet?

So, when can we start using HTTP/3 and QUIC for real? Not quite yet, but hopefully soon. There is a large number of mature open source implementations and the major browsers have experimental support. However, most of the typical servers have suffered some delays: nginx is a bit behind other stacks, Apache hasn’t announced official support, and NodeJS relies on OpenSSL, which won’t add QUIC support anytime soon. Even so, we expect to see HTTP/3 and QUIC deployments rise throughout 2021.

HTTP/3 and QUIC are highly advanced protocols with powerful performance and security features, such as a new HTTP prioritization system, HOL blocking removal, and 0-RTT connection establishment. This sophistication also makes them difficult to deploy and use correctly, as has turned out to be the case for HTTP/2. We predict that early deployments will mainly be done via the early adoption of CDNs such as Cloudflare, Fastly, and Akamai. This will probably mean that a large part of HTTP/2 traffic can and will be upgraded to HTTP/3 automatically in 2021, giving the new protocol a large traffic share almost out of the box. When and if smaller deployments will follow suit is more difficult to answer. Most likely, we will continue to see a healthy mix of HTTP/3, HTTP/2, and even HTTP/1.1 on the web for years to come.

Conclusion

This year, HTTP/2 has become the dominant protocol, serving 64% of all requests, having grown by 10 percentage points during the year. Home pages have seen a 13% increase in HTTP/2 adoption, leading to an even split of pages served over HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2. Using a CDN to serve your home page pushes HTTP/2 adoption up to 80%, compared with 30% for non-CDN usage. There remain some older servers, Apache and IIS, that are proving resistant to upgrading to HTTP/2 and TLS. A big success has been the decrease in website connection usage due to HTTP/2 connection multiplexing. The median number of connections in 2016 was 23 compared to 13 in 2020.

HTTP/2 prioritization and server push have turned out to be way more complex to deploy at large. Under certain implementations they show clear performance benefits. There is, however, a significant barrier to deploying and tuning existing servers to use these features effectively. There are still a large proportion of CDNs who do not support prioritization effectively. There have also been issues with consistent browser support.

HTTP/3 is just around the corner. It will be fascinating to follow the adoption rate, see how discovery mechanisms evolve, and find out which new features will be deployed successfully. We expect next year’s Web Almanac to see some interesting new data.