Capabilities

Introduction

Progressive Web Apps (PWA) are a cross-platform application model based on web technology. With the help of Service Workers, these applications run even when the user is offline. The Web App Manifest allows users to add a PWA to their home screen or program list. When opened from there, a PWA appears as a native application. However, PWAs can only use the functions and capabilities that are exposed through web platform APIs. Arbitrary native interfaces cannot be called, leaving a gap between native applications and web apps.

The Capabilities Project, informally also known as Project Fugu, is a cross-company effort by Google, Microsoft, and Intel to bridge the gap between web and native. This is important to keep the web relevant as a platform. To do so, the Chromium contributors implement new APIs exposing capabilities of the operating system to the web, while maintaining user security, privacy, and trust. These capabilities include, but are not limited to:

- File System Access API for accessing files on the local file system

- File Handling API for registering as a handler for certain file extensions

- Async Clipboard API to access the user’s clipboard

- Web Share API for sharing files with other applications

- Contact Picker API to access contacts from the user’s address book

- Shape Detection API for efficient detection of faces or barcodes in images

- Web NFC, Web Serial, Web USB, Web Bluetooth, and other APIs (for the entire list, see the Fugu API Tracker)

Anyone can propose a new capability by creating a ticket in the Chromium bug tracker. The Chromium contributors examine the proposals and discuss all APIs with other developers and browser vendors through the appropriate standards bodies. Meanwhile, the Fugu team implements the API in Chromium, where it is initially implemented behind a flag. Later in the process, the API is made available to a limited audience via an origin trial. During this phase, developers can sign up for a token to test the API on a specific origin. If the API turns out to be robust enough, the API ships in Chromium and, if the vendors decide so, other browsers. The Capability Status site shows where the different Capability APIs are in the process.

Project Fugu, the codename of the Capabilities Project, is named after a Japanese dish: correctly prepared, the meat of the blowfish is a special taste experience. If prepared incorrectly, however, it can be fatal. The powerful APIs of Project Fugu are extremely exciting for developers. However, they can affect the security and privacy of the user. Therefore, the Fugu team pays special attention to these issues. For instance, new interfaces require the website to be sent over a secure connection (HTTPS). Some of them require a user gesture, such as a click or key press, to prevent fraud. Other capabilities require explicit permission by the user. Developers can use all APIs as a progressive enhancement: by feature detecting the APIs, applications won’t break in browsers lacking support for those capabilities. In browsers that support them, users can get a better experience. This way, web apps progressively enhance according to the user’s particular browser.

This chapter gives an overview of various modern web APIs, and the state of web capabilities in 2020 based on usage data by the HTTP Archive and Chrome Platform Status. Since some interfaces are brand-new, their (relative) usage is very low. So, unlike most chapters, HTTP Archive usage stats will be presented as the absolute numbers of pages rather than relative percentages. Due to technical limitations, the HTTP Archive only has data available for APIs that require neither permission, nor a user gesture. Where no data is available, the percentage of page loads in Google Chrome according to Chrome Platform Status will be shown instead. Even if some figures are so small that the statistics are not necessarily meaningful, in many cases trends can still be read from the data. Also, these stats can be used as a baseline for future annual editions of this chapter, looking back to see how much the APIs have matured and improved their adoption. Unless otherwise noted, the APIs are only available in Chromium-based browsers, and their specifications are in the early stages of standardization.

Async Clipboard API

With the help of the document.execCommand() method, websites could already access the user’s clipboard. However, this approach is somewhat restricted, as the API is synchronous (making it difficult to process clipboard items), and it can only interact with selected text in the DOM. This is where the Async Clipboard API (W3C Working Draft) comes in. This new API is not only asynchronous, meaning it doesn’t block the page for large chunks of data or waiting for a permission to be granted, but it also allows for images to be copied to or pasted from the clipboard in supported browsers such as Chrome, Edge, and Safari.

Read Access

The Async Clipboard API provides two methods for reading content from the clipboard: a shorthand method for plain text, called navigator.clipboard.readText(), and a method for arbitrary data, called navigator.clipboard.read(). Currently, most browsers only support HTML content and PNG images as additional data formats. As the clipboard may contain sensitive data, reading from it requires the user’s consent.

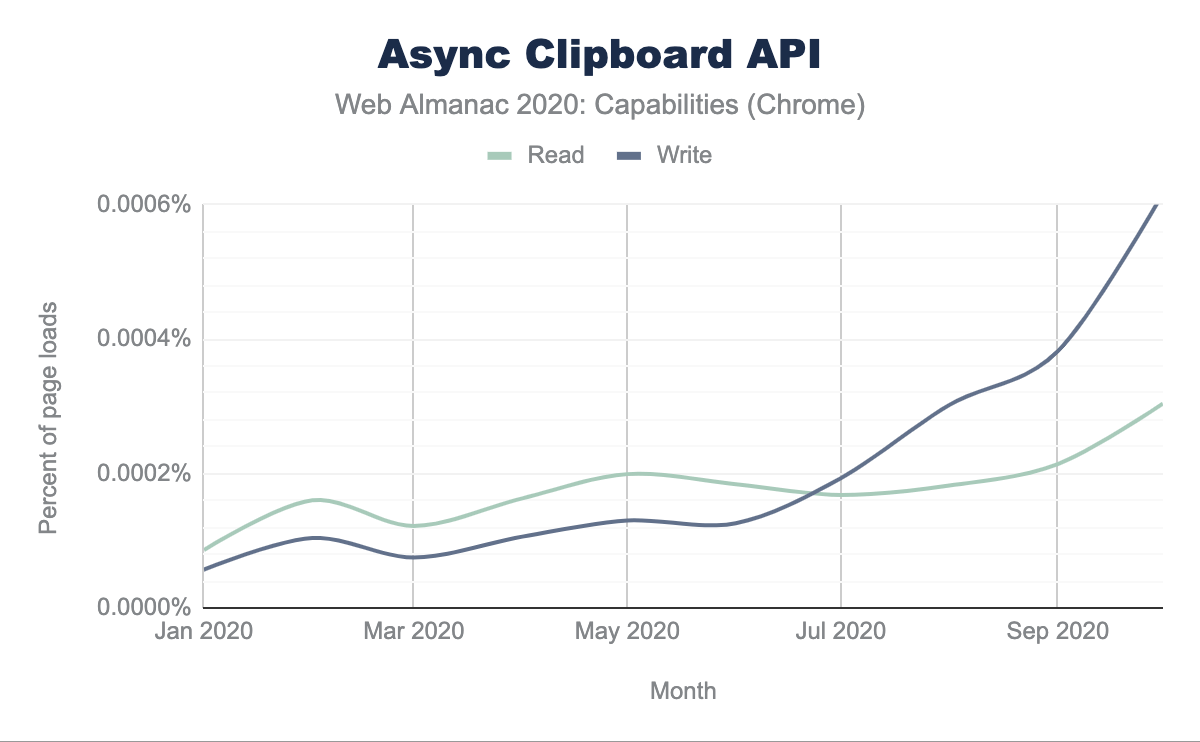

(Sources: Async Clipboard Read, Async Clipboard Write)

The Async Clipboard API is comparatively new, so its usage is currently rather low. In March 2020, Safari added support for the Async Clipboard API in Safari 13.1. Over the course of 2020, the usage of the read() API was growing. In October 2020, the API was called during 0.0003% of all page loads in Google Chrome.

Write Access

Apart from reading operations, the Async Clipboard API also offers two methods for writing content to the clipboard. Again, there’s a shorthand method for plain text, called navigator.clipboard.writeText(), and one for arbitrary data called navigator.clipboard.write(). In Chromium-based browsers, writing to the clipboard while the tab is active does not require permission. Trying to write to the clipboard when the website is in the background does, however. As this method requires a user gesture and permission first, it’s not covered by the HTTP Archive metrics. In contrast to the read() method, the write() method shows an exponential growth in usage, being part of 0.0006% of all page loads in October 2020.

The Raw Clipboard Access API, another Fugu capability, might even further enhance the Async Clipboard API by allowing arbitrary data to be copied from or pasted to the clipboard.

StorageManager API

Web browsers allow users to store data on the user’s system in different ways, such as Cookies, the Indexed Database (IndexedDB), the Service Worker’s Cache Storage, or Web Storage (Local Storage, Session Storage). In modern browsers, developers can easily store hundreds of megabytes and even more, depending on the browser. When browsers run out of space, they can clear data until the system is no longer over the limit, which can lead to data loss.

Thanks to the StorageManager API, which is part of the WHATWG Storage Living Standard, browsers no longer behave like a black box in that regard. This API allows developers to estimate the remaining space available and opt-in to persistent storage, meaning that the browser will not clear a website’s data when disk space is low. Therefore, the API introduces a new StorageManager interface on the navigator object, currently available on Chrome, Edge, and Firefox.

Estimate the available storage

Developers can estimate the available storage by calling navigator.storage.estimate(). This method returns a promise resolving to an object with two properties: usage shows the number of bytes used by the application and quota contains the maximum number of bytes available.

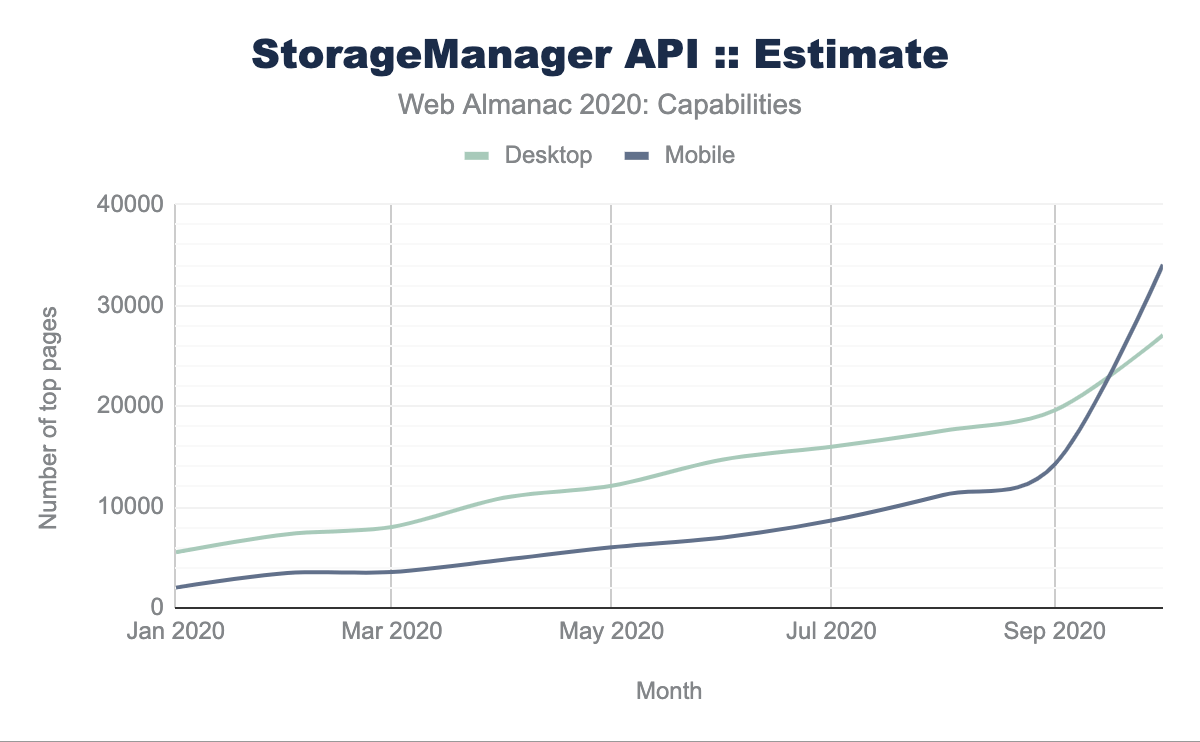

The Storage Manager API is supported in Chrome since 2016, Firefox since 2017, and the new Chromium-based Edge. HTTP Archive data shows that the API is used on 27,056 desktop pages (0.49%) and 34,042 mobile pages (0.48%). Over the course of 2020, the usage of the Storage Manager API kept growing. This also makes this interface the most commonly used API in this chapter.

Opt-in to persistent storage

There are two categories of web storage: “Best Effort” and “Persistent”, with the first being the default. When a device is low on storage, the browser automatically tries to free up best effort storage. For instance, Firefox and Chromium-based browsers evict storage from the least recently used origins. This, however, poses a risk of losing critical data. To prevent eviction, developers can opt for persistent storage. In this case, the browser will not clear the storage, even when space is low. Users can still choose to clear up the storage manually. To opt for persistent storage, developers need to call the navigator.storage.persist() method. Depending on the browser and site engagement, a permission prompt may show, or the request will automatically be accepted or denied.

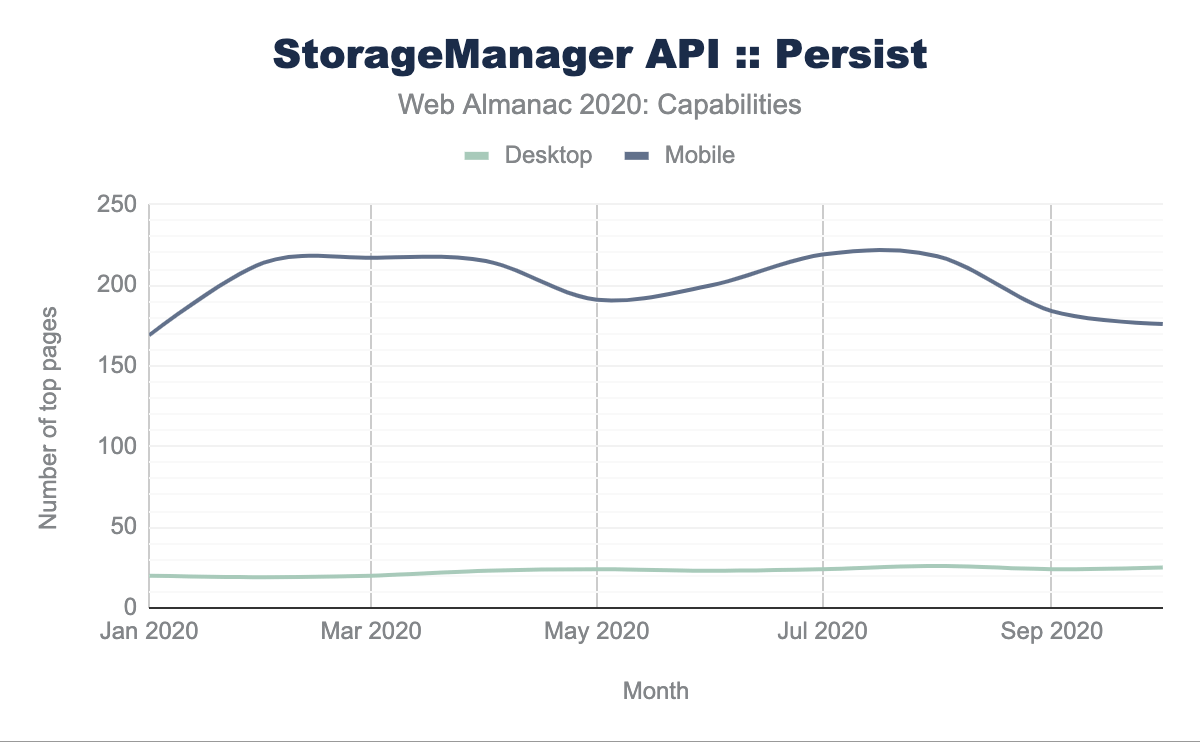

The persist() API is less often called than the estimate() method. Only 176 mobile pages make use of this API, compared to 25 desktop websites. While usage on the desktop seems to remain at this low level, there is no clear trend on mobile devices.

New Notification APIs

With the help of the Push and Notifications APIs, web applications have long been able to receive push messages and display notification banners. However, some parts were missing. Until now, push messages had to be sent via the server; they could not be scheduled offline. Also, web applications installed to the system could not show badges on their icon. The Badging and Notification Triggers APIs enable both scenarios.

Badging API

On several platforms, it’s common for applications to present a badge on the application’s icon indicating the amount of open actions. For instance, the badge could show the number of unread emails, notifications, or to-do items to complete. The Badging API (W3C Unofficial Draft) allows installed web applications to show such a badge on its icon. By calling navigator.setAppBadge(), developers can set the badge. This method takes a number to be shown on the application’s badge. The browser then takes care of displaying the closest possible representation on the user’s device. If no number is specified, a generic badge will be shown (e.g., a white dot on macOS). Calling navigator.clearAppBadge() removes the badge again. The Badging API is a great choice for email clients, social media apps, or messengers. The Twitter PWA makes use of the Badging API to show the number of unread notifications on the application’s badge.

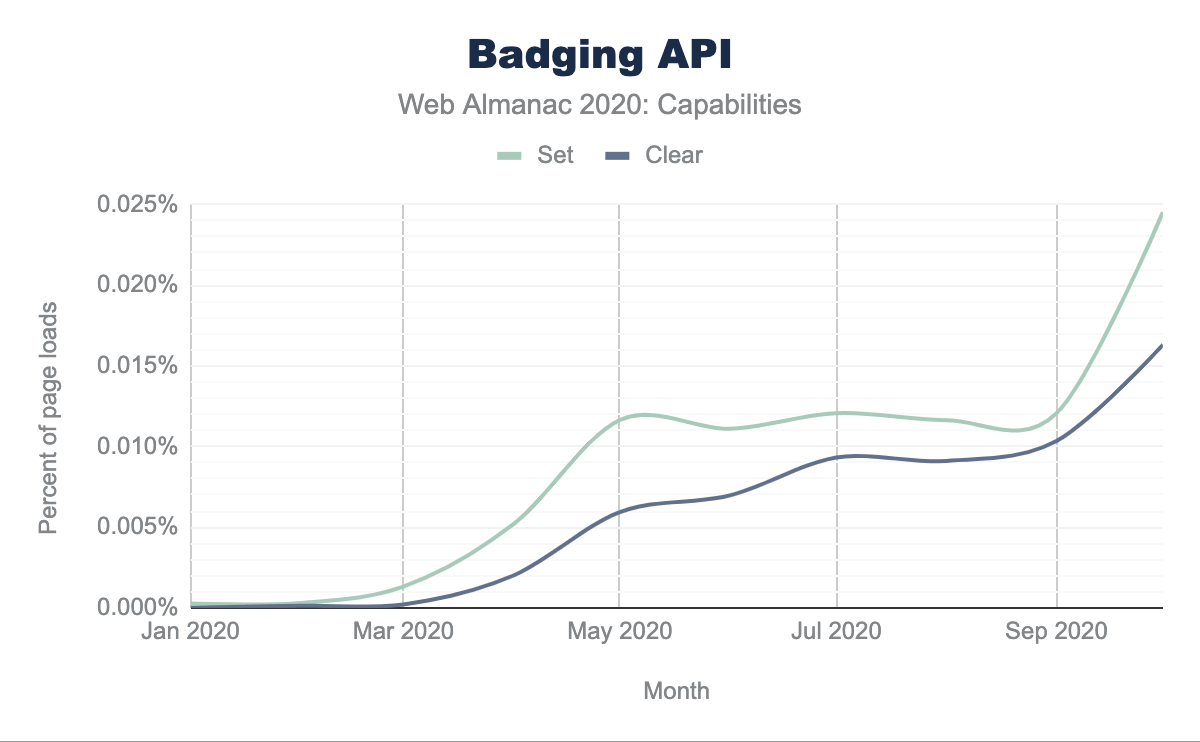

(Sources: Badge Set, Badge Clear)

In April 2020, Google Chrome 81 shipped the new Badging API, followed by Microsoft Edge 84 in July. After Chrome shipped the API, the usage numbers shot up. In October 2020, on 0.025% of all page loads in Google Chrome, the setAppBadge() method is called. The clearAppBadge() method is less often called, during around 0.016% of page loads.

Notification Triggers API

The Push API requires the user to be online to receive a notification. Some applications, such as games, reminder or to-do apps, calendars, or alarm clocks, could also determine the target date for a notification locally and schedule it. To support this feature, the Chrome team is experimenting with a new API called Notification Triggers (Explainer, not on a standards track yet). This API adds a new property called showTrigger to the options map that can be passed to the showNotification() method on the Service Worker’s registration. The API is designed to allow for different kinds of triggers in the future, albeit for now, only time-based triggers are implemented. For scheduling a notification based on a certain date and time, developers can create a new instance of a TimestampTrigger and pass the target timestamp to it:

registration.showNotification('Title', {

body: 'Message',

showTrigger: new TimestampTrigger(timestamp),

});(Source: Notification Triggers)

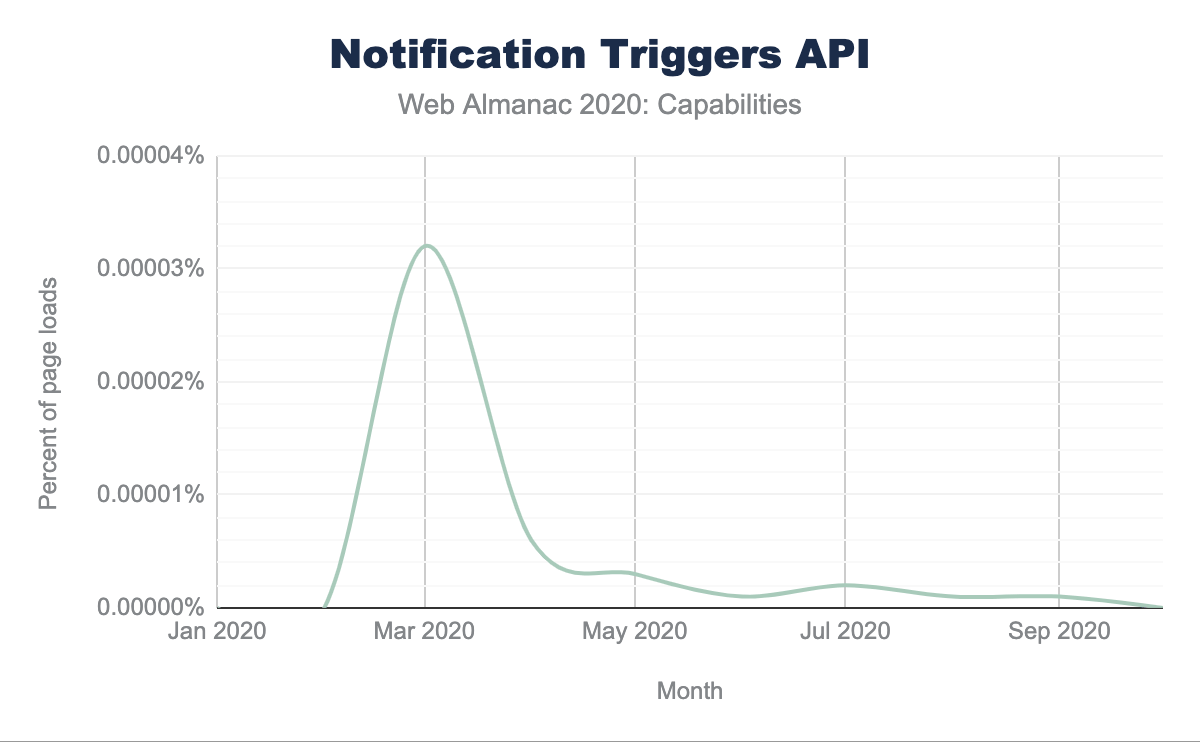

The Fugu team first experimented with Notification Triggers in an origin trial from Chrome 80 to 83, pausing development afterwards due to the lack of feedback by developers. Starting from Chrome 86 released in October 2020, the API has entered the origin trial phase again. This also explains the usage data of Notification Triggers API that peaked at being called on 0.000032% of page loads in Chrome during the first origin trial at around March 2020.

Screen Wake Lock API

To save energy, mobile devices darken the screen backlight and eventually turn off the device’s display, which makes sense in most cases. However, there are scenarios where the user may want the application to explicitly keep the display awake, for instance, when reading a recipe while cooking or watching a presentation. The Screen Wake Lock API (W3C Working Draft) solves this problem by providing a mechanism to keep the screen on.

The navigator.wakeLock.request() method creates a wake lock. This method takes a WakeLockType parameter. In the future, the Wake Lock API could provide other lock types, such as turning the screen off, but keeping the CPU on. For now, the API only supports screen locks, so there is just one optional argument with the default value of screen. The method returns a promise that resolves to a WakeLockSentinel object. Developers need to store this reference to call its release() method and release the screen wake lock later on. The browser will automatically release the lock when the tab is inactive, or the user minimizes the window. Also, the browser may deny a request and reject the promise, for example due to low battery.

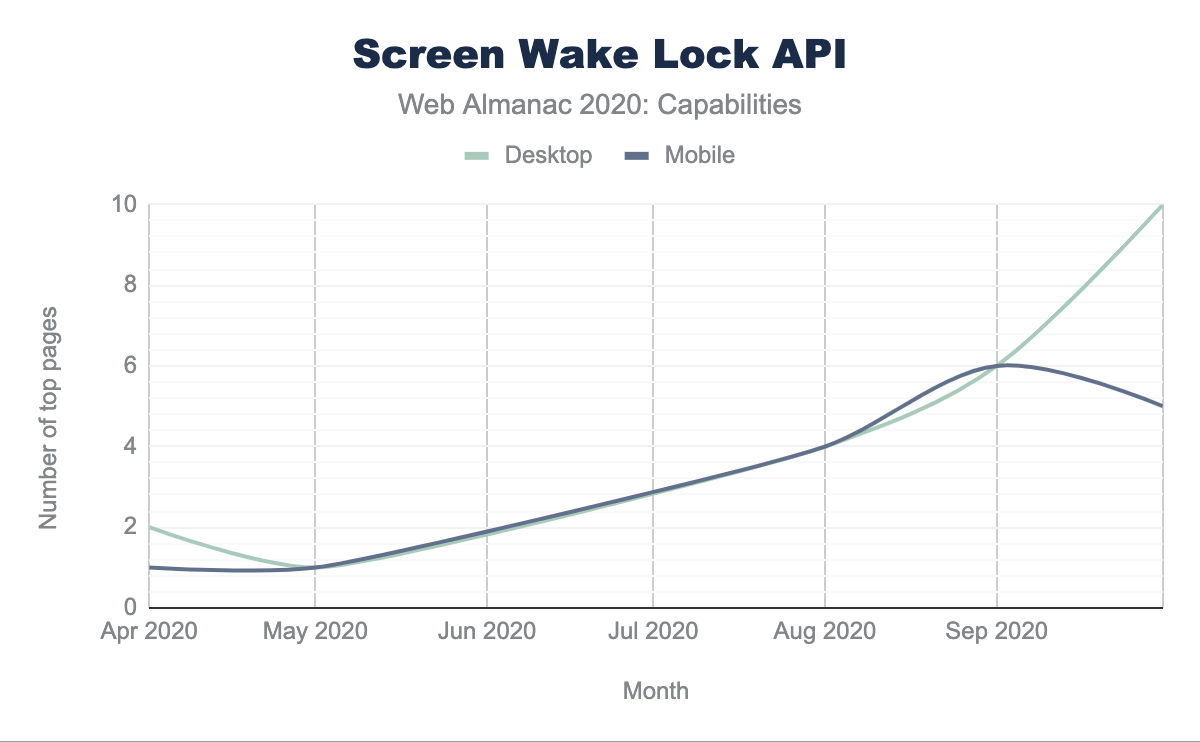

BettyCrocker.com, a popular cooking website in the US, offers their users an option to prevent the screen from going dark while cooking with the help of the Screen Wake Lock API. In a case study, they published that the average session duration was 3.1 times longer than normal, the bounce rate reduced by 50%, and purchase intent indicators increased by about 300%. The interface therefore has a directly measurable effect on the success of the website or application, respectively. The Screen Wake Lock API shipped with Google Chrome 84 in July 2020. The HTTP Archive only has data for April, May, August, September and October. After the release of Chrome 84, usage rose quickly. In October 2020, the API was adopted on 10 desktop and 5 mobile pages.

Idle Detection API

Some applications need to determine if the user is actively using a device or if they are idle. For instance, chat applications may display that the user is absent. There are various factors that can be taken into account, such as a lack of interaction with the screen, mouse, or keyboard. The Idle Detection API (WICG Draft Community Group Report) provides an abstract API that allows developers to check if either the user is idle or the screen locked, given a certain threshold.

To do so, the API provides a new IdleDetector interface on the global window object. Before developers can use this functionality, they have to request permission by calling IdleDetector.requestPermission() first. If the user grants the permission, developers can create a new instance of IdleDetector. This object provides two properties: userState and screenState, containing the respective states. It will raise a change event when either the user’s or the screen’s state change. Finally, the idle detector needs to be started by calling its start() method. The method takes a configuration object with two parameters: a threshold defining the time in milliseconds that the user has to be idle (the minimum is a minute), and developers can optionally pass an AbortSignal to the abort property, which serves to abort idle detection later on.

(Source: Idle Detection)

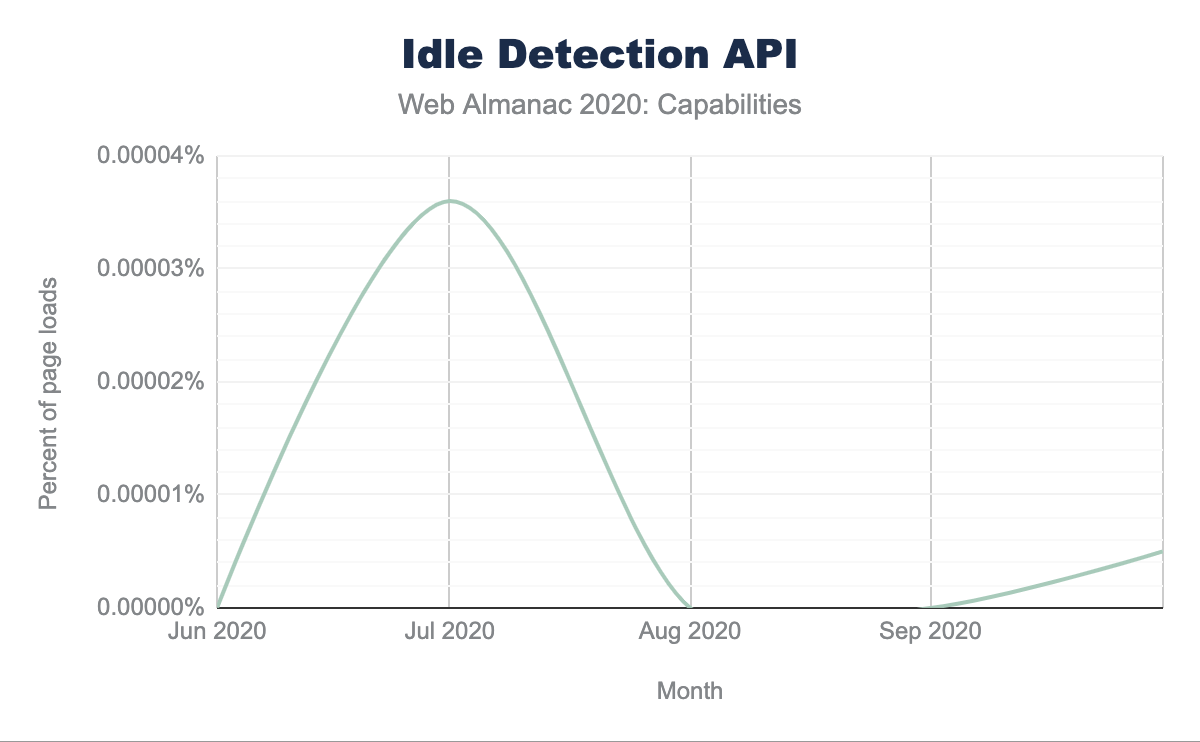

At the time of this writing, the Idle Detection API is in an origin trial, so its API shape may change in the future. For the same reason, its usage is very low and hardly measurable.

Periodic Background Sync API

When the user closes a web application, it cannot communicate with its backend service anymore. In some cases, developers might still want to synchronize data on a more or less regular basis, just as native applications can. For instance, news applications might want to download the latest headlines before the user wakes up. The Periodic Background Sync API (WICG Draft Community Group Report) strives to bridge this gap between web and native.

Register for periodic sync

The Periodic Background Sync API relies on Service Workers that can run even when the app is closed. As with other capabilities, this API requires users’ permission first. The API implements a new interface called PeriodicSyncManager. If present, developers can access an instance of this interface on the Service Worker’s registration. To synchronize data in the background, the application has to register first, by calling periodicSync.register() on the registration. This method takes two parameters: a tag, which is an arbitrary string to recognize the registration again later on, and a configuration object that takes a minInterval property. This property defines the desired minimum interval in milliseconds by the developer. However, the browser ultimately decides how often it will actually invoke background synchronization:

registration.periodicSync.register('articles', {

minInterval: 24 * 60 * 60 * 1000 // one day

});Respond to a periodic sync interval

For each tick of the interval, and if the device is online, the browser triggers the Service Worker’s periodicsync event. Then, the Service Worker script can perform the necessary steps to synchronize the data:

self.addEventListener('periodicsync', (event) => {

if (event.tag === 'articles') {

event.waitUntil(syncStuff());

}

});At the time of this writing, only Chromium-based browsers implement this API. On these browsers, the application has to be installed first (i.e., added to the homescreen) before the API can be used. The site engagement score of the website defines if and how often periodic sync events can be invoked. In the current conservative implementation, websites can sync content once a day.

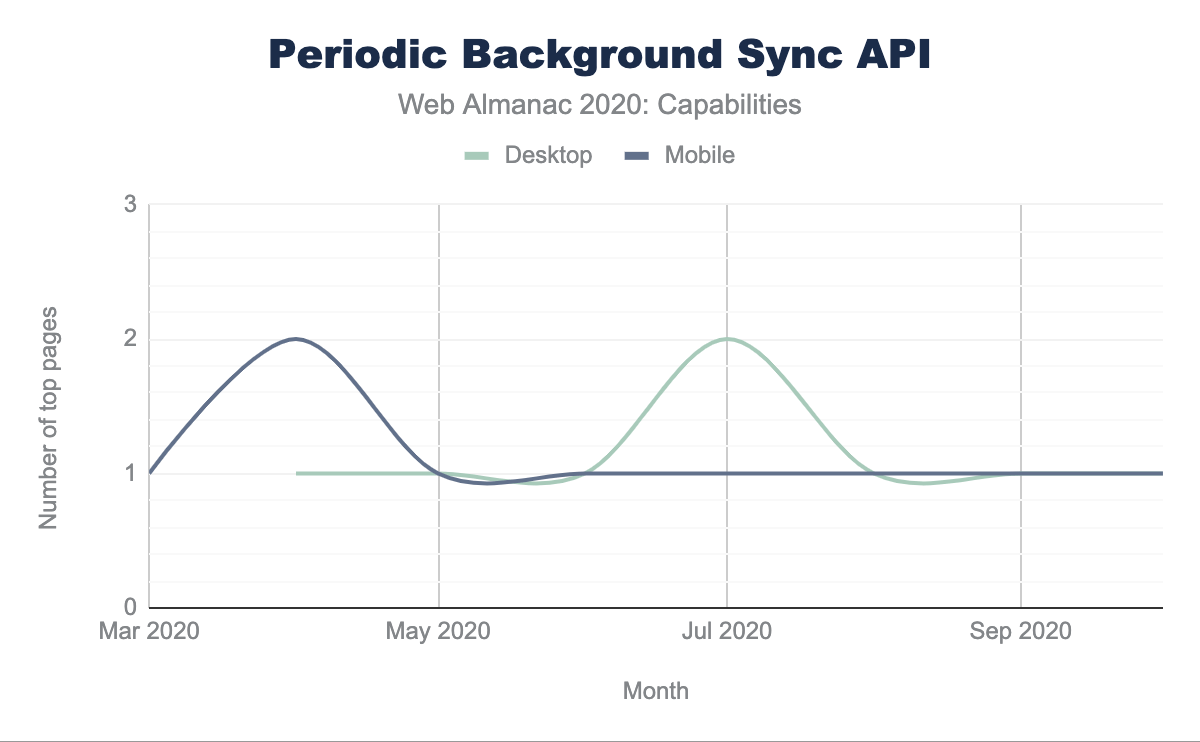

The use of the interface is currently very low. Over 2020, only one or two pages monitored by HTTP Archive made use of this API.

Integration with native app stores

PWAs are a versatile application model. However, in some cases, it may still make sense to offer a separate native application: for example, if the app needs to use features that are not available on the web, or based on the programming experience of the app developer team. When the user already has a native app installed, apps might not want to send notifications twice or promote the installation of a corresponding PWA.

To detect if the user already has a related native application or PWA on the system, developers can use the getInstalledRelatedApps() method (WICG Draft Community Group Report) on the navigator object. This method is currently provided by Chromium-based browsers and works for both Android and Universal Windows Platform (UWP) apps. Developers need to adjust the native app bundles to refer to the website and add information about the native app(s) to the Web App Manifest of the PWA. Calling the getInstalledRelatedApps() method will then return the list of apps installed on the user’s device:

const relatedApps = await navigator.getInstalledRelatedApps();

relatedApps.forEach((app) => {

console.log(app.id, app.platform, app.url);

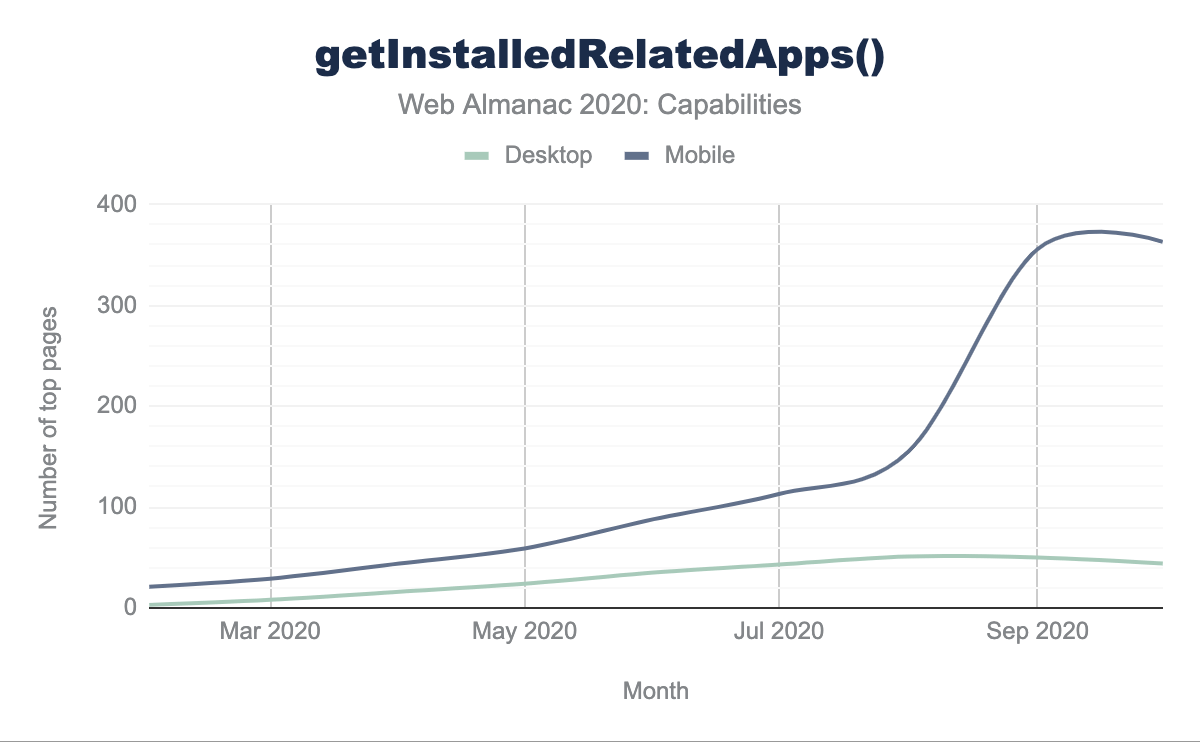

});getInstalledRelatedApps() usage, based on the number of pages monitored by HTTP Archive. It compares the usage on mobile and desktop devices. It shows a steady growth for mobile devices, peaking at 363 pages in October 2020 compared to 44 desktop pages.getInstalledRelatedApps().

Over the course of 2020, the getInstalledRelatedApps() API shows a steady growth on mobile websites. In October, 363 mobile pages tracked by the HTTP Archive made use of this API. On desktop pages, the API does not grow quite as fast. This could also be due to Android stores currently providing significantly more apps than the Microsoft Store does for Windows.

Content Indexing API

Web apps can store content offline using various ways, such as Cache Storage, or IndexedDB. However, for users it’s hard to discover which content is available offline. The Content Indexing API (WICG Editor’s Draft) allows developers to expose content more prominently. Currently, Chrome on Android is the only browser to support this API. This browser shows a list of “Articles for you” in the Downloads menu. Content indexed via the Content Indexing API will appear there.

The Content Indexing API extends the Service Worker API by providing a new ContentIndex interface. This interface is available via the index property of the Service Worker’s registration. The add() method allows developers to add content to the index: Each piece of content must have an ID, a URL, a launch URL, title, description, and a set of icons. Optionally, the content can be grouped into different categories such as articles, home pages, or videos. The delete() method allows for removing content from the index again, and the getAll() method returns a list of all indexed entries.

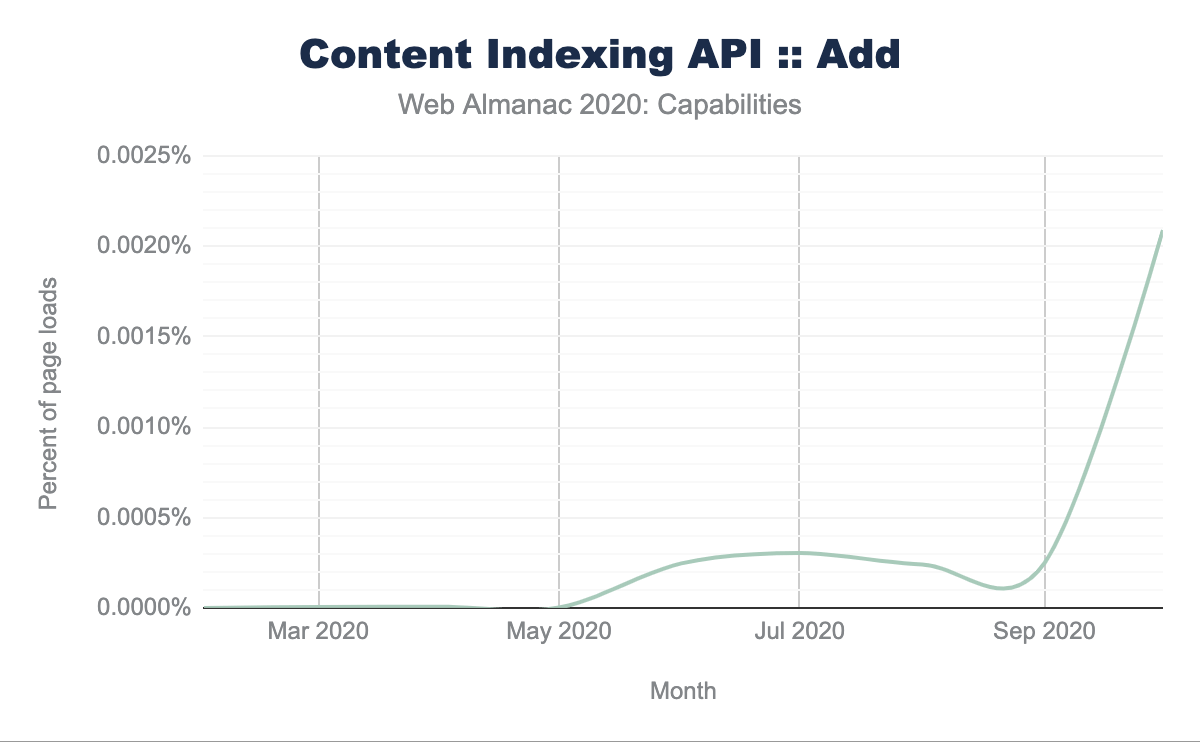

(Source: Content Indexing)

The Content Indexing API launched with Chrome 84 in July 2020. Directly after shipping, the API was used during approximately 0.0002% of page loads in Chrome. In October 2020, this value has increased almost tenfold.

New Transport APIs

Finally, there are two new transport methods that are currently in origin trial. The first one allows developers to receive high-frequency messages with WebSockets, while the second one introduces an entirely new bidirectional communication protocol apart from HTTP and WebSockets.

Backpressure for WebSockets

The WebSocket API is a great choice for bidirectional communication between websites and servers. However, the WebSocket API does not allow for backpressure, so applications dealing with high-frequency messages may freeze. The WebSocketStream API (Explainer, not on the standards track yet) wants to bring easy-to-use backpressure support to the WebSocket API by extending it with streams. Instead of using the usual WebSocket constructor, developers need to create a new instance of the WebSocketStream interface. The connection property of the stream returns a promise that resolves to a readable and writable stream that allow to obtain a stream reader or writer, respectively:

const wss = new WebSocketStream(WSS_URL);

const {readable, writable} = await wss.connection;

const reader = readable.getReader();

const writer = writable.getWriter();The WebSocketStream API transparently solves backpressure, as the stream readers and writers will only proceed if it’s safe to do so.

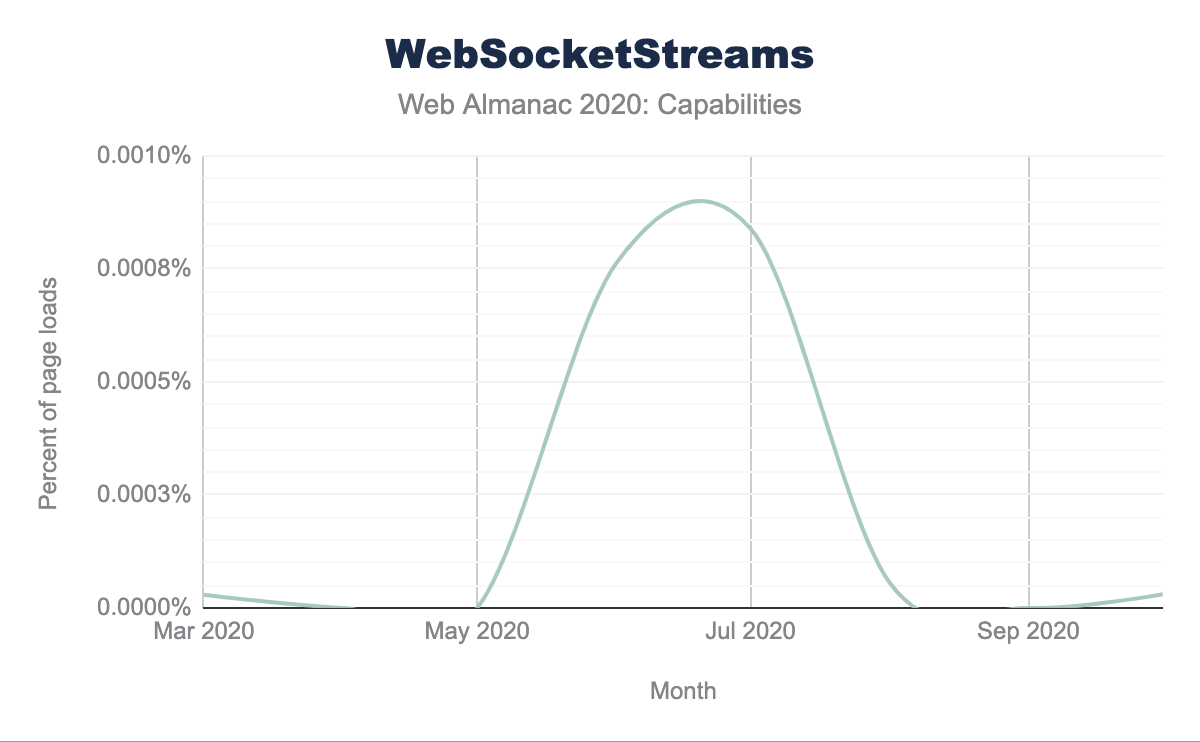

(Source: WebSocketStream)

The WebSocketStream API has completed its first origin trial and is now back in the experimentation phase again. This also explains why the usage of this API currently is so low that it’s hardly measurable.

Make it QUIC

QUIC (IETF Internet-Draft) is a multiplexed, stream-based, bidirectional transport protocol implemented on UDP. It’s an alternative to HTTP/WebSocket APIs that are implemented on top of TCP. The QuicTransport API is the client-side API for sending messages to and receiving messages from a QUIC server. Developers can choose to send data unreliably via datagrams, or reliably by using its streams API:

const transport = new QuicTransport(QUIC_URL);

await transport.ready;

const ws = transport.sendDatagrams();

const stream = await transport.createSendStream();QuicTransport is a valid alternative to WebSockets, as it supports the use cases from the WebSocket API and adds support for scenarios where minimal latency is more important than reliability and message order. This makes it a good choice for games and applications dealing with high-frequency events.

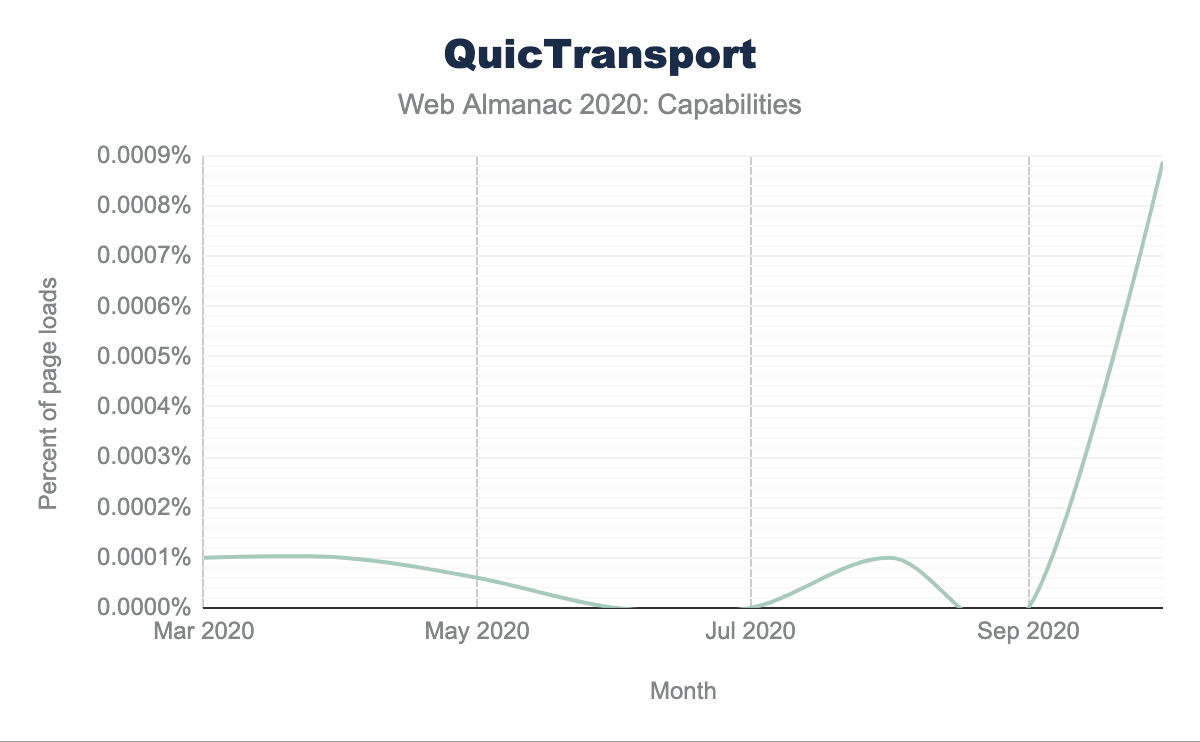

(Source: QuicTransport)

The use of the interface is currently still so low that it’s hardly measurable. In October 2020, it has increased strongly and is now used during 0.00089% of page loads in Chrome.

Conclusion

The state of web capabilities in 2020 is healthy, as new, powerful APIs regularly ship with new releases of Chromium-based browsers. Some interfaces like the Content Indexing API or Idle Detection API help to add finishing touches to certain web applications. Other APIs, such as the File System Access and Async Clipboard API, allow a whole new application category, namely productivity apps, to finally fully make the shift to the web. Some APIs such as Async Clipboard and Web Share API have already made their way into other, non-Chromium browsers. Safari even was the first mobile browser to implement the Web Share API.

Through its rigorous process, the Fugu team ensures that access to these features takes place in a secure and privacy-friendly manner. Additionally, the Fugu team actively solicits the feedback from other browser vendors and web developers. While the usage of most of these new APIs is comparatively low, some APIs presented in this chapter show an exponential or even hockey stick-like growth, such as the Badging or Content Indexing API. The state of web capabilities in 2021 will depend on the web developers themselves. The author encourages the community to build great web applications, make use of the powerful APIs in a backwards-compatible manner, and help make the web a more capable platform.